How to Talk About Population Health

Fred ZimmermanElsewhere on the Blog you can find a definition of population health. A useful starting place, for sure, but no place you’d care to end up. Population health is one of the concepts that acquires its meaning as much from how we talk about it as what we say. In these polarizing political times, it is essential that we find a way to discuss population health that unites rather than divides.

In 2010, The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation released a report entitled

A New Way to Talk about the Social Determinants of Health, which begins with this insight:

“It turns out that trying to figure out how to say something simply can be a complicated process.”

Indeed! That’s why it’s always worth choosing our words carefully. The report offers concrete techniques to help bring your audience on board with the idea that creating health is a collective project, one that we all have a stake in and some control over. It contains many useful suggestions for phrasing, such as appealing to universally-shared values, like equal opportunity or investing in children. Another good tip is avoiding jargon.

Of course, it’s easy to point out things not to do. But what do effective examples of talking about population health look like? These three statements were shown in focus groups to be more effective in communicating our message than the usual jargon.

- All Americans should have the opportunity to make the choices that allow them to live a long, healthy life, regardless of their income, education or ethnic background.

- The opportunity for health begins in our families, neighborhoods, schools and jobs.

- Your neighborhood or job shouldn’t be hazardous to your health.

The report also suggests updating our literature by replacing terms like “social determinants of health” with plain language that appeals to a broader American audience. For example, instead of discussing “health disparities,” we can talk about giving everyone a chance to live a healthy life. Other replacement suggestions include:

- Replacing “low-income workers” with “hard-working Americans who have gotten squeezed in tough times”;

- Replacing “poverty” with “Americans struggling to get by”, and

- Replacing “refugees” and “immigrants” with “people seeking a new home in America” or “children caught between two worlds”.

Changes such as these may seem minor or might appear to make concepts less concise, but they make a big difference in lasting comprehension. Psychological research shows that abstract concepts like “social health disparities” that take even a split second longer for our minds to process are less likely to be believed and/ or remembered.

This mirrors advice given by Joe Romm in his superb book, Language Intelligence. It’s a great book, and a short and very entertaining read. (But if video is your medium, there’s also this YouTube synopsis). Romm was named by Time magazine as “the web’s most influential climate change blogger,” so in addition to being an accomplished physicist, he also knows something about effective communication. Joe makes the point that short, memorable arguments and phrases win arguments regardless of their truth or falsity. I thought about this insight a great deal during the presidential election, and even considered writing up a prediction on this basis. After the election’s results were announced, I immediately assigned Joe’s book in my class on public health ethics.

In short, most of this advice boils down to two points:

- Use words that are short and common

- Use words that appeal to shared values

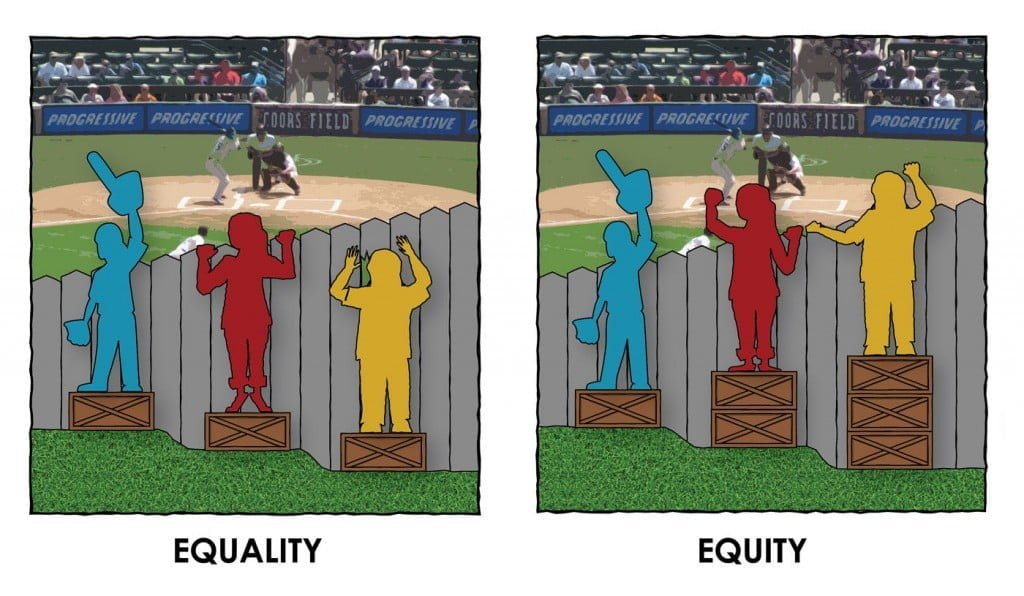

The book also emphasizes that how we talk and write carries content beyond just what we write. When we always write about “he” and never “she,” we exclude. When we say that healthcare (or obesity or racism) is complex—and then use long sentences with arcane jargon to make it complex—we’re producing a subtle but powerful argument against action. And when we use a clear likeable metaphor—like children looking over a fence that is taller for some than others as a metaphor of challenges to equity—we create allies.

I have come to understand that communication is the very essence of social justice.

All comments will be reviewed and posted if substantive and of general interest to IAPHS readers.