Crossroads Clientcare Longitudinal Database: Community-Engaged Data Collection for Population Health

Tammy Leonard, Sandi PruittRecently we talked with Dr. Sandi Pruitt and Dr. Tammy Leonard about their engagement in CARE, a community academic partnership improving the lives of low -and middle-income residents through evidence-based research. We also discussed their groundbreaking new data resource that emerged from and serves this partnership, the Crossroads Clientcare Longitudinal Database (CCLD), and how it represents a vision for what they call Community-Engaged Data collection, an important source of new science on the health impacts of food assistance delivery programs, and a resource for population health researchers and change makers.

Can you tell us more about this community academic partnership?

CARE developed because collaboration is required to develop and execute research that is meaningful and impactful for ensuring that all households have an opportunity to meet their basic needs. CARE stimulates collaborations between people, places, and organizations to support more comprehensive solutions for disadvantaged, underserved populations in Dallas County and for the organizations that serve them. CARE leverages interdisciplinary collaboration to facilitate:

- Documentation of unmet needs in underserved populations

- Research agendas aligned with the needs of underserved populations and the organizations that serve them

- Communication of results to help the public and policymakers understand the problems and needs of the underserved

Currently, CARE’s focus is a state-of-the-science, first-in-the-nation longitudinal health and economic assessment of food pantry clients. This will lead to better representation of people who are food insecure in health and healthcare research, intervention, and policy. This work is possible due to a large, multi-sectoral partnership with other institutions working to improve the lives of the food insecure in Dallas, Texas. It relies on the principles of participatory research, wherein clients inform the goals and needs of the populations they represent. This approach strives to improve the welfare of the food insecure population through an integrative approach to thinking about diverse services (e.g. financial, health, food).

One of the exciting developments in food redistribution emerging from Dallas was the Community Delivery Partners (CDP) model – can you tell us how you leveraged the implementation of this new model of service delivery to conduct new research?

The CDP model was developed by Crossroads Community Services, one of our community partners in the CARE community academic partnership. Typically, food assistance is distributed using a “hub” model: there is one large food pantry location where all clients go to pick up food. The CDP model is an innovation that uses additional sites at community partner locations in order to geographically expand and spread out the available pickup locations for clients. These CDP sites are usually small and unable to serve as a full-fledged food pantry with refrigeration and storage, often due to financial, infrastructure, and resource barriers.

CARE is currently funded by a RWJF Evidence for Action project to evaluate the CDP model’s impacts on client health and economic outcomes. CARE is studying whether delivery via a traditional hub model versus the “hub and spoke” CDP model is associated with varying food assistance use and differences in client health outcomes. Preliminary findings suggest that the hub-and-spoke CDP delivery model seems to increase the frequency that clients visit (by reducing travel burden), thus increasing their food security.

How might community development partners affect client’s health?

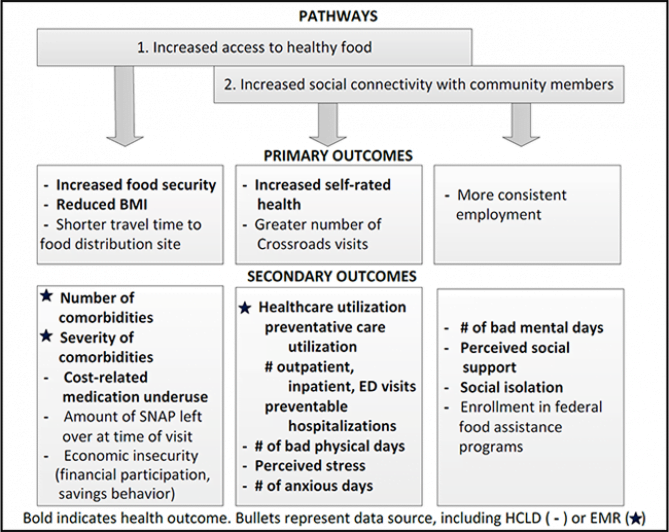

We hypothesize in our work that increased access to food assistance through a hub-and-spoke delivery model using CDPs could improve health through several pathways, including increased access to healthy food, and increased social connectivity with community members. These pathways are illustrated here in a conceptual model.

Why was the Crossroads Clientcare Longitudinal database (CCLD) developed?

The CCLD developed out of our community academic partnership in order to meet a major data gap. Without data on food pantry clients (how often they visit, who they are, what economic and health challenges they face, body mass index, what kind of food they receive, etc.) our partnership wasn’t able to evaluate the impact of food pantry assistance on client outcomes. Most food banks and pantries evaluate one major outcome: number of pounds of food provided. Many don’t even count the number of unique clients receiving food; in many cases, they aren’t able to since they don’t have any IT infrastructure or expertise in database design. Our data fills this gap, and as the data continue to accumulate, we can better understand the needs of food pantry clients. We can also better evaluate client outcomes associated with food pantry assistance and how programmatic changes in how food is distributed might help clients improve their health and wellbeing. We also hope that our approach to data collection can serve as a model for others seeking to take a more data-driven approach to understanding challenges faced by vulnerable populations.

What kind of data are collected, and how have you used data linkages to extend the value of the CCLD for research?

The CCLD consists of data collected by Crossroads Community Services or one of their participating Community Distribution Partners on low-income households in Dallas County who receive food. The data are longitudinal, allowing us to follow outcomes from the same household over time. We currently have records for 7,260 unique households who received food from May 22, 2013 to April 27, 2018. Data collection is ongoing, and annual updates are made to the CCL Database each May, when new clients and new observations about existing clients are added.

Data are collected about food received, sociodemographic and employment characteristics of the household, and self reports of depressive symptoms, chronic disease prevalence, cigarette smoking, self-reported health, and social and emotional support; these data are geocoded. Body mass index is collected at each visit using a scale and stadiometer. We have also linked these data to electronic medical record (EMR) data from a large safety-net healthcare system, and to publicly available data at the neighborhood level and housing-parcel level residential appraisal data, to better assess neighborhood socioeconomic context and healthcare utilization and health outcomes.

Where can readers learn more about the CCLD or creating their own Community Engaged Data collection project?

De-identified data may be obtained from Crossroads Community Services Research Program. Alternatively, please contact Tammy Leonard (Tammy.Leonard@unt.edu) or Sandi Pruitt (sandi.pruitt@utsouthwestern.edu) for more information about joining the CARE partnership and gaining access to CCLD data. We also have provided access to training materials, our database monitoring checklist, CARE publications, and other resources.

Watch for a follow-up post this summer with results.

All comments will be reviewed and posted if substantive and of general interest to IAPHS readers.