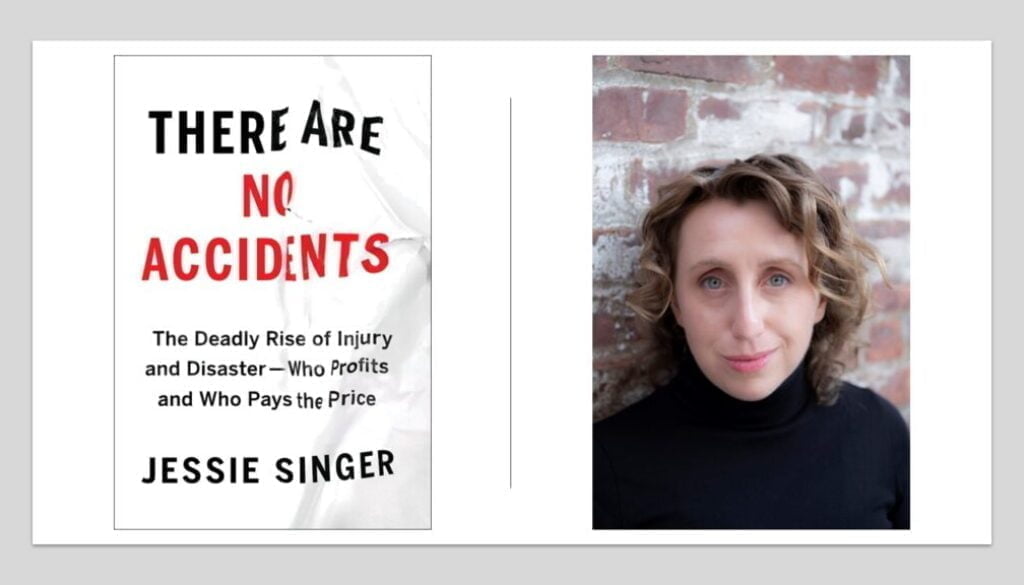

There Are No Accidents: An Interview with Author Jessie Singer, Part 3

Jarron Saint OngeWe welcome Jessie Singer to the IAPHS Blog to discuss their new book, There Are No Accidents: The Deadly Rise of Injury and Disaster—Who Profits and Who Pays the Price. In this book, Singer discusses the importance and implications of the way we report, frame, and respond to accidents and accident-related deaths.

Following is the final part of the 3-part series (see Part 1 and Part 2). The interviews have been lightly edited and condensed for space and clarity.

How you go about using health research in your work? I want to think about how we can better communicate to journalists.

Mostly, I read a huge amount. I talked to a lot of epidemiologists. I kept an ear out for what was interesting, and I read a lot of history. Much of this history appears forgotten, more or less. For example, in the 1960s, William Haddon, the first administrator of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), was talking about far more advanced ideas in terms of injury epidemiology than NHTSA talks about today. We’ve lost a lot of this advancement over time.

So, what can we all do to better communicate?

In academic research, abstracts matter so much more than you think. I read thousands of abstracts to write this book — making a judgement call from that basis whether to read on further. Like many authors and journalists, I was on an impossible deadline — I had two years to write this book while working a day job — so if I could not figure an article out from the abstract, I had to move on, and thus maybe losing access to really powerful research.

I would also recommend translating your statistics, wherever you can, into talking points that can be comprehensible to a layperson, because otherwise as a journalist, I have to do that math, and I might not have the technical skills to do so, or I could screw it up, or simply might move on from that research for that lack of accessibility.

I would consider having a non-expert read anything that’s up for publication. Do they understand it? There are huge parts of academic studies I cite where I don’t understand everything about the methodology. But I understand the conclusions. If the conclusion is not comprehensible to a layman, then there’s no way that your research is going to communicate to policymakers and journalists.

What is our role as population health scientists and practitioners in reducing accidents?

Understanding how and what you measure matters. I recommend questioning tradition. As an example, economists traditionally measure traffic fatalities as a rate of the vehicle miles traveled. So, while the total number of traffic fatalities has been rising for a decade, traffic fatalities appear to going down by economists’ measures, because miles traveled keep going up. By that measure, where we keep driving more and dying less, it could seem like we’re doing good, when of course, inherent is that statement is that mobility comes with a requisite death toll that we are perfectly okay with; that to move people, some number must die preventable deaths — even though we know this is not true, we know that these deaths are preventable.

Another transportation example of how what you measure matters: Engineers typically catalogue traffic fatalities and traffic crashes by environmental factors, such as rain; mechanical errors, such as faulty brakes; or human errors, such as speeding or distraction. So, they would look at 10,000 traffic crashes, and would say that 94% were caused by human error — it wasn’t raining, the car worked fine, but the human erred. This decision about what to measure fails to look at all of those roads that all of those crashes happened on, or the design and planning policies in those places. It fails to ask: If all those drivers are making the same mistake on the same road, how do those roads look different than other roads where no one’s making those errors? How can we traffic engineers control error?

When we measure individual factors rather than environmental factors, we’re already defining the problem and the policy answer — because the only answer we have to individual errors is policing, and this saves the time, money, and responsibility of powerful actors to change the environment, fix the road, regulate the corporation, re-open the hospital, etc. You can change the built environment to change the behavior, but it’s much easier for governments and corporations to convince us that the problem is bad people, not the place where those people made a mistake.

What we need is the political will to eschew blame and embrace harm reduction. IAPHS members can provide the data to do that. But involves asking the right questions, and being purposeful in defining the problem.

There Are No Accidents: The Deadly Rise of Injury and Disaster—Who Profits and Who Pays the Price is available now from Simon and Schuster publishing.

All comments will be reviewed and posted if substantive and of general interest to IAPHS readers.