Sick Individuals and Sick Countries: COVID-19

Fred ZimmermanThere’s been a lot of attention directed toward early mortality estimates for SARS-CoV-2, pointing out, for example, that mortality rates are highest for the elderly, while hospitalizations are more evenly distributed across ages.

Yet these estimates are of the determinants of susceptibility, not the determinants of prevalence. And these are different. So what drives the large differences in prevalence of Covid-19 across different populations?

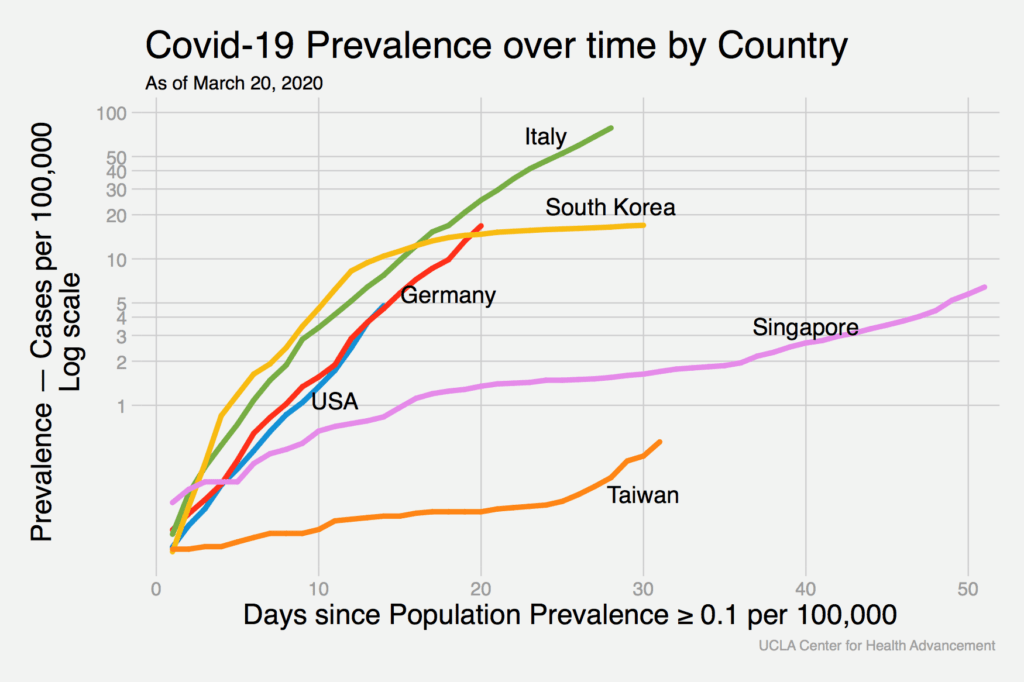

To try to gain at least some intuition on this question, I’ve graphed the prevalence of Covid-19 for several countries over time. The data are all from the relevant Wikipedia page on the 2020 Coronavirus Pandemic for each country. Because the virus entered different countries at different times, the x-axis shows the time since the prevalence first exceeded 0.1 per 100,000.

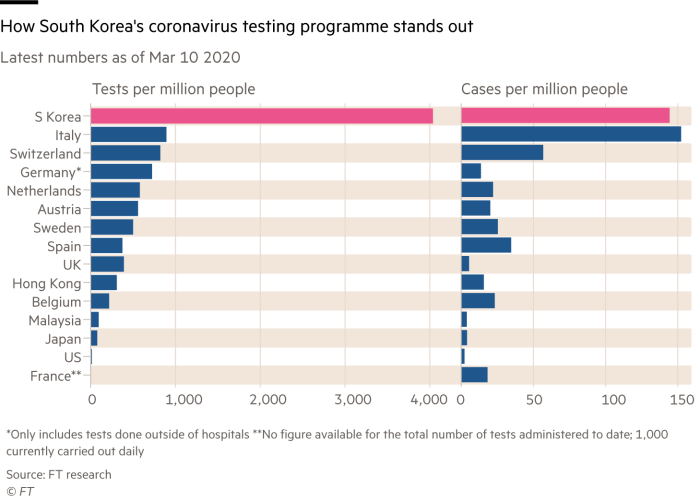

I’m hoping the hive mind can help provide some insight on these patterns. For example, that bend for South Korea happens on March 1st. So what happened in South Korea on or around March 1st? President Moon Jae-in gave a forceful speech on that day in which he declared, “The government is now waging all-out responses after raising the crisis alert to the highest level.” South Korea has pursued free and widespread testing, and has cancelled major events. In addition, GPS information about the whereabouts of people diagnosed with Covid-19 is publicly available. Is this what it takes?

Other clues may come from Taiwan and Singapore, both countries with a far lower trajectory for prevalence than others. Both countries were very proactive early on, testing everyone early—including those who tested negative for flu, which is how community transmission was first uncovered in Taiwan. By contrast, the US policy of testing only those in certain risk categories is guaranteed never to expand the risk categories. That was a key conceptual mistake early on that surely delayed an effective policy response.

But beyond that, life has gone on somewhat more normally, at least in Taiwan, where schools have clever dividers between desks , but otherwise remain open for now. And this raises its own point: severe measures were taken in China, and now in Italy. Early, but not as severe, measures were taken in Taiwan and Singapore. Same health threat, different responses, different outcomes, at least so far.

People in the US have been asked to make enormous sacrifices, altering or foregoing personal connections, putting education on hold and altering all kinds of daily routines. The US economy is about to plunge off a cliff and that will pose its own problems for population health, including enormous risks of mental health problems, drug abuse, interpersonal violence, and so on. Such sacrifices are widely embraced as necessary, but why? Of course one answer is that they are necessary to protect health and prevent this risk of transmission. But another, equally valid, answer is that such sacrifices are necessary now primarily because the earlier policy response was inadequate. Same question, different lenses, different answers.

Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea are remarkable success stories, at least so far. It appears that radical social distancing is not required to limit the spread of coronavirus, but a competent and prepared governmental response right from the very beginning is critical.

What elements of preparedness do you think we should have in place to protect population health the next time this happens? Please feel free to add your thoughts in the comments!

All comments will be reviewed and posted if substantive and of general interest to IAPHS readers.