Interpreting Conflict in the Past: Applying the Dirty War Index to a Bioarchaeological Setting

Petra BanksMore and more, researchers are beginning to appreciate the importance of studying the effects of conflict on population health. As physical anthropologists looking for ways to assess violence against non-combatant civilians, we discovered the “Dirty War Index” (DWI), first introduced by Hicks and Spagat (2008). Used to determine the ‘dirtiness’ of combat, the DWI is generally considered a modern public health tool. However, we also found it effective in looking at past conflict, when paired with bioarchaeological methods and historic research. Recently, we have conducted a couple of case studies using the DWI, including one on the twenty-first century Syrian Civil War, and another on the mid-nineteenth century Mountain Meadows Massacre in Utah.

The DWI is a simple ratio that empirically assesses “dirty” acts. This allows us to compare trends across different combatant groups, combat events, and armed conflicts. The denominator is the total potential times a certain undesirable action COULD occur, and the numerator is how many times it DID occur. For example, to assess the number of prisoners tortured, one would place the total number of prisoners taken in the denominator, and the total number of prisoners tortured in the numerator. A DWI of 100 would be extremely ‘dirty,’ and a DWI of 0 would be perfectly ‘clean.’ Using this approach gives us the opportunity to compare combat events in a concrete way, in an attempt to understand which events were the ‘dirtiest.’

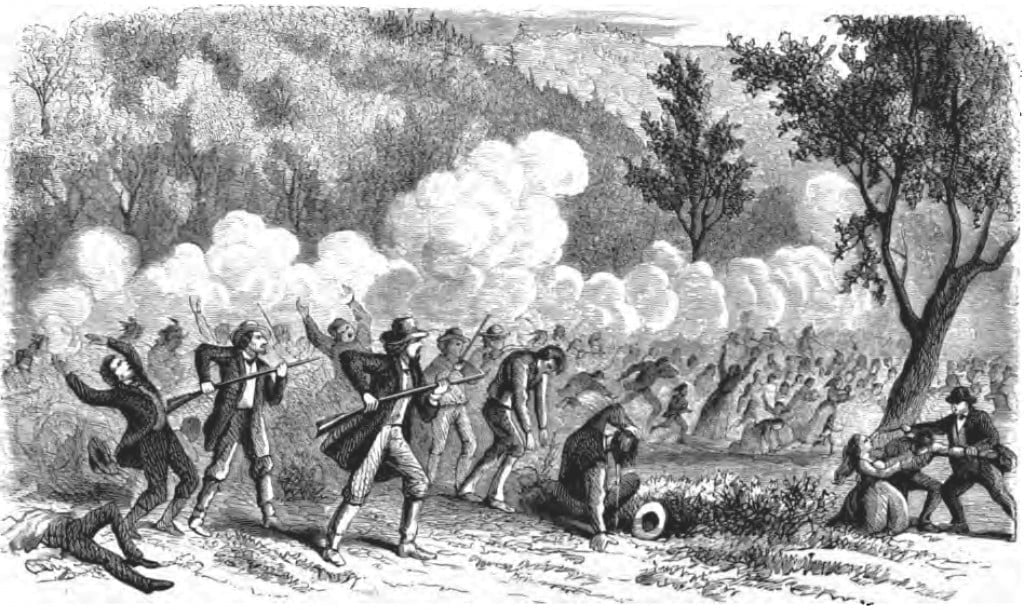

This method was ideal for our research, because of its adaptability to the different cultural and societal norms of the past. In the results from our case studies, we found that the DWI can yield more detailed, or even different, results than accepted reports. For example, although published epidemiological analyses demonstrate overall harm to children, our Syrian War case study showed a more precise picture of which combatant groups cause the most harm. In comparing child deaths from chemical weapons, the Syrian Army generated a DWI of 13.2, and non-state-armed groups (NSAGs) generated a DWI of 0. In our historic case study, we looked at the Mountain Meadows Massacre, an incident from 1857 in which nearly an entire wagon train was killed at the hands of local settlers. The DWI analysis painted a very different picture from the popular news of the time, which described the settlers as brutal “child killers.” Although the DWI for other violent actions was extremely high (in some cases 100), the DWI for child mortality was low; only 3.57. These case studies indicate that the DWI may provide details either missed by different methods of analysis or left out by political and historical accounts. The latter example also highlights the exaggeration and distortion of facts that frequently occurs for emotional or political reasons when reporting news. By using counts to examine the severity of an event, the DWI cuts through political and emotional hyperbole.

In short, our results emphasize the potential empirical value of the DWI as a method for evaluating the morality of armed conflicts by quantifying their effects on various aspects of population health. They also demonstrate the adaptability of the method when applied to past conflicts, expanding the possible political interpretations of events. In present terms, the DWI is a means of drawing attention to the atrocities of war and encouraging methods of prevention and avoidance for the future.

Hicks MH-R, Spagat M (2008) The Dirty War Index: A public health and human rights tool for examining and monitoring armed conflict outcomes. PLoS Med 5:e243

Molly Zuckerman and Petra Banks have an upcoming chapter with Michelle Davenport and Ryan King examining trauma and recidivistic trauma in individuals with chronic syphilis in post-medieval London. This chapter will be published in Broken Bones, Broken Bodies: Bioarchaeology and Forensic Approaches of Accumulative Trauma and Violence edited by Caryn Tegtmeyer and Debra Martin. In addition, Molly Zuckerman, together with Anna Osterholtz, will be organizing an invited session at the 2018 AAAs which will gather scholars to present works focused on the approaches, advantages, disadvantages, and future of the integrating of methods and theory from public health into biological anthropology, specifically into bioarchaeology and paleopathology. Petra Banks is currently working towards completion of her Master’s thesis examining patterns of blast trauma in skeletal remains.

Molly K Zuckerman: Molly K. Zuckerman is an associate professor in the Department of Anthropology and Middle Eastern Cultures at Mississippi State University. She earned her BA degrees in Anthropology and Women’s Studies at Pennsylvania State University, and her MA and PhD in Anthropology at Emory University. Her research interests include the evolution and disease ecology of infectious disease, with a focus in treponemal disease, the reconstruction of social identity from human skeletal remains, diagnostic methods in paleopathology, the study of ancient disease, and epidemiologic transitions.

Molly K Zuckerman: Molly K. Zuckerman is an associate professor in the Department of Anthropology and Middle Eastern Cultures at Mississippi State University. She earned her BA degrees in Anthropology and Women’s Studies at Pennsylvania State University, and her MA and PhD in Anthropology at Emory University. Her research interests include the evolution and disease ecology of infectious disease, with a focus in treponemal disease, the reconstruction of social identity from human skeletal remains, diagnostic methods in paleopathology, the study of ancient disease, and epidemiologic transitions.

All comments will be reviewed and posted if substantive and of general interest to IAPHS readers.