Engaging Underserved Populations for Chronic Disease Screening and Prevention in Non-Healthcare Settings

Gbenga Ogedegbe, Nadia Islam, Joseph RavenellIf we rely on the traditional clinical approach to improving outcomes for populations known to be less likely to seek healthcare, we are going to miss those who most need our help. Efforts to improve population health are more effective when interventions are culturally tailored and designed for the settings and contexts where people live, work, pray, and play. All too often, people who need health screenings and services do not routinely visit traditional sites of healthcare delivery, leaving them at risk for complications from undiagnosed chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and certain cancers.

At NYU Langone’s Department of Population Health, we work with a diverse set of community partners, as well as national and global stakeholders, to help connect underserved and diverse populations with essential care in non-healthcare settings. We are committed to research aimed at informing local practice and policies—always with an eye to scale and sustainability. Below are some scalable examples of our work.

The Intersection of Haircuts, Church, and Health

Hypertension is the world’s top killer, and African Americans are substantially more likely to develop high blood pressure than white people are. Roughly 40 percent of black men and women have high blood pressure. By age 55, the rate jumps to 75 percent .

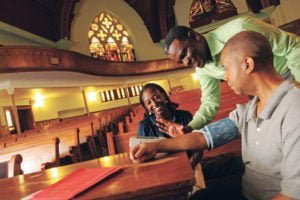

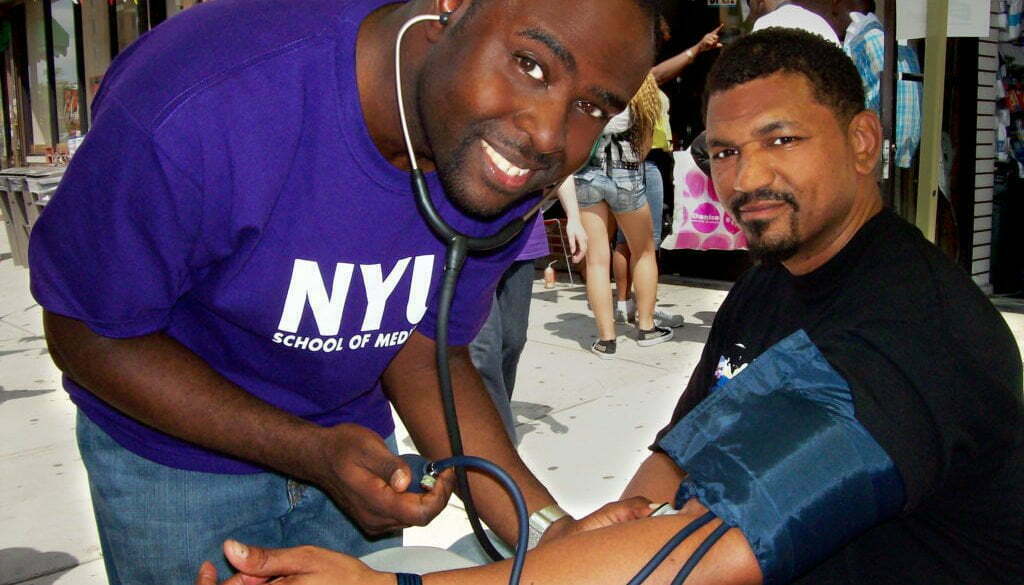

Black men in particular face increased risk of death from colorectal cancer and complications from hypertension—yet they have lower rates of preventive colonoscopies and blood pressure control because of poor access and an uneven experience due to mistrust and stereotype threat within the healthcare system. To address this problem, we realized we needed to meet these men in their communities, where they might be more receptive to discussing their health. Thanks to funding from the Men’s Health Initiative, created with funding from the National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control Prevention, we trained trusted members of the community to become patient navigators and deploy them to barbershops and churches. These patient navigators, or community health workers, engaged with men about their risk factors and steered them towards colon cancer screenings and follow-up care.

We conducted a series of randomized trials studying the effectiveness of this approach. Findings published in the American Journal of Public Health indicated that when African American men teamed up with patient navigators they met in barbershops, they were twice as likely to complete screening for colorectal cancer as those men who were given a list of screening facilities.

In another study that tested the effectiveness of this approach in faith-based settings, we found that after six months, people who met regularly with patient navigators at church saw a net reduction of 5.8 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure . If sustained over five years, that drop can reduce heart attacks, stroke, and heart failure by at least 20 percent.

Innovative Approaches to Diabetes Management among New York City’s Bangladeshi Community

Similar to our work in barbershops and churches, our Center for the Study of Asian American Health (CSAAH) has developed a number of community-based interventions that build bridges between communities and healthcare systems. With funding from the National Institutes on Minority Health and Health Disparities, CSAAH is currently the only Center of its kind in the U.S. that is solely dedicated to research on Asian American health and health disparities. We work with more than 55 Asian American community, government, business and academic/medical partners. All our community partners are equal stakeholders in our projects—from inception through implementation.

Through our Diabetes Research, Education, and Action for Minorities (DREAM) Project, we design and implement ways to improve diabetes control and diabetes-related health complications in the Bangladeshi community in New York City. We recruit members of the Bangladeshi community as community health workers (CHWs), or health coaches, who meet regularly with Bangladeshi immigrants with type 2 diabetes– in their homes, social services agencies, mosques, or workplaces–to provide education on lifestyle and diet, as well as connect them with education, screening, and care through a culturally adapted protocol. After six months, we found that a higher proportion of individuals who received the full CHW intervention achieved diabetes control compared to those who did not (36.6 percent versus 25.6 percent, respectively). Study participants also reported improvements in diabetes knowledge, physical activity, and health self-efficacy.

we design and implement ways to improve diabetes control and diabetes-related health complications in the Bangladeshi community in New York City. We recruit members of the Bangladeshi community as community health workers (CHWs), or health coaches, who meet regularly with Bangladeshi immigrants with type 2 diabetes– in their homes, social services agencies, mosques, or workplaces–to provide education on lifestyle and diet, as well as connect them with education, screening, and care through a culturally adapted protocol. After six months, we found that a higher proportion of individuals who received the full CHW intervention achieved diabetes control compared to those who did not (36.6 percent versus 25.6 percent, respectively). Study participants also reported improvements in diabetes knowledge, physical activity, and health self-efficacy.

In addition, our team developed toolkits to implement sustainable, organizational-level health promotion and prevention strategies as part of a large-scale Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-funded program called REACH FAR (Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health for Asian Americans). The toolkits are designed to implement evidence-based and culturally tailored strategies to enhance cardiovascular health and promote access to healthy foods in community settings.

For example, the program implemented a volunteer-led blood pressure screening program in 15 faith-based organizations serving Asian American populations across NYC. Early evaluation results demonstrate that individuals with hypertension who are engaged with the program experience improvements in blood pressure control. These toolkits—available in English, Bengali, Hindi, Nepali, Punjabi, Korean, Tagalog, and Urdu–are resources for community-based organizations, places of worship, or program evaluators and academic researchers interested in ways to prevent high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease.

Our work has important policy implications. Deploying CHWs and lay community members in a range of community-based settings to assist with health promotion and prevention efforts is an effective and low-cost tool for implementing evidence-based public health practices.

Today, the majority of community health worker programs are grant funded, but efforts are underway to consider sustainable mechanisms for reimbursements across a variety of health and community settings. We are partnering with payer organizations to examine the impact of adding CHWs to primary care teams’ efforts on health outcomes like blood pressure and associated healthcare costs.

When designed and implemented effectively, community-based interventions not only build bridges between communities and healthcare systems, they can also build bridges between communities and other social services sectors by addressing issues related to immigration, housing, labor, and other social determinants of health. Expanding reimbursement models to include such interventions–including community health workers—is crucial in creating better health outcomes, expanding community capacity, and reducing health disparities.

All comments will be reviewed and posted if substantive and of general interest to IAPHS readers.