Conference Highlight: Health Happens in State Houses

Fred ZimmermanAs our eyes are on Washington, DC, our bodies are being shaped by what happens in state capitols. That’s the message I took away from several of the talks at the recent IAPHS conference in Austin.

Dawn Alley from the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation talked about the accountable health communities model as well as several state initiatives, such as their effort to partner with state and local governments to improve whole-child health. Jo Ivey Boufford of the New York Academy of Medicine presented a fascinating effort to link public health, medical care delivery, and state agencies into a network whose members are all pulling in the same direction and all accountable to the same data. And one of the most exciting talks was in the same session, when Rachel Kimbro of the Kinder Institute’s Urban Data Platform walked us through the rich thickets of health and other contextual data about Houston that they Institute has acquired and made available on their website.

In these and many other talks, it became clear that a lot of the energy around policy-making relevant to population health has shifted to the states and local governments. The antics in DC still get a lot of attention—appropriately—but just as health happens in communities, health policy, too, is local.

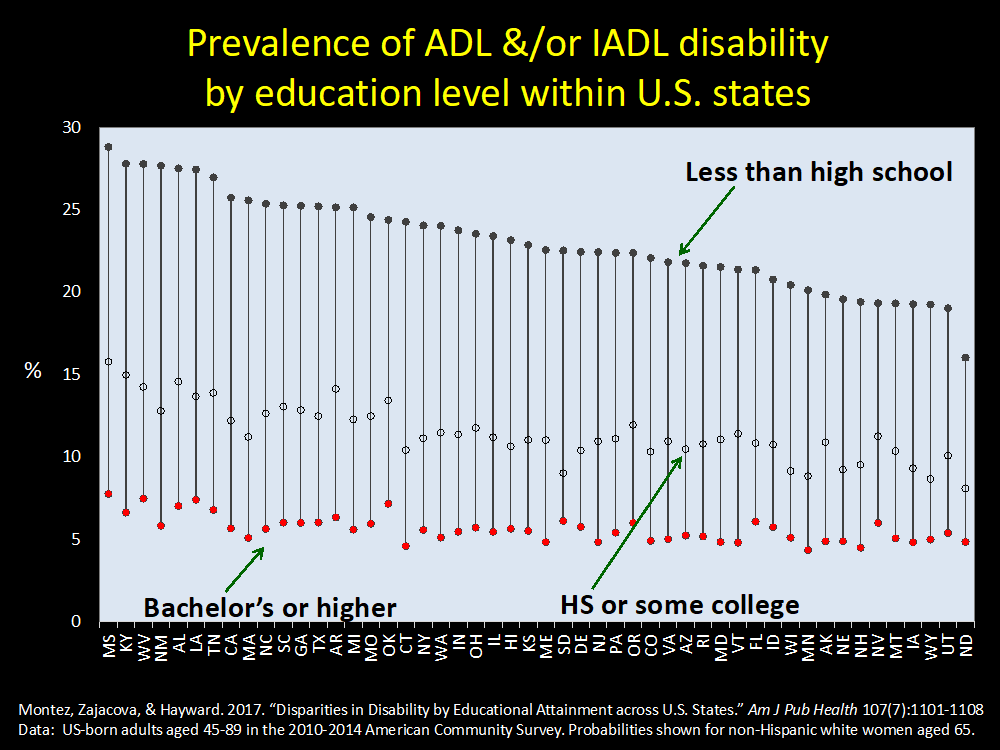

One presentation in particular really drove this point home. Jennifer Karas Montez of Syracuse University presented her work with Anna Zajacova and Mark Hayward on the role of state context for understanding educational disparities in mortality across states. We all know that there is a meaningful health gradient in education, with individuals with higher education achieving better health than those with less education. But this gradient is not equal across all states.

Using disability as a lens, Karas Montez showed that while rates of impairment in activities of daily living among those with a bachelor’s degree were similar across all states, these rates varied substantially for those with less than a high-school education. In fact, for those with this low level of education, the rate of experiencing difficulty with ADLs among the 5 worst-performing states was about 27% , while among the 5 best-performing states it was only about 18%. While education clearly matters to health, how much it matters varies by state.

Karas Montez went on to highlight some of the particular state policies that either buffer or exacerbate the effects of social disadvantage on health. Because this work is ongoing, I can’t tell you what the answers are, but I can tell you to stay tuned! There are some really interesting things states can do to promote more equitable population health.

In the meantime, check out Karas Montez’s brand-new commentary in AJPH in which she discusses these issues. Comparing the large and increasing divergence in life expectancy between New York and Mississippi, she notes, “In terms of life expectancy, New York now resembles Denmark, and Mississippi resembles Romania.” State policies matter, she says, citing major differences between New York and Mississippi on the Earned Income Tax Credit, cigarette taxes, and Medicaid expansion.

Karas Montez concludes, as did this set of talks, that if we’re interested in population health we should spend less time focusing on individual behavior and more time examining the political-economic context. We should “hypothesize upward” to the state policies that really matter.

All comments will be reviewed and posted if substantive and of general interest to IAPHS readers.