Book Review: The Lives of Community Health Workers – Local Labor and Global Health in Urban Ethiopia

Susan WatkinsBook review: The Lives of Community Health Workers: Local Labor and Global Health in Urban Ethiopia, by Kenneth Maes, published by Routledge

This deeply researched, intelligent, and persuasive book by Dr. Kenneth Maes addresses the moral economy of global aid for health.

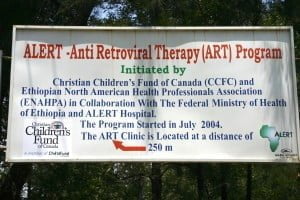

To fill the role of community health workers (CHWs), many poor countries extend the reach of their under-resourced public health systems by recruiting and training unpaid volunteers from poor, marginalized communities. The book describes the work of these volunteer CHWs in urban Ethiopia who willingly accept the task given to them: to provide care and support for their neighbors living with AIDS. What makes their unpaid work remarkable is that volunteers are themselves often struggling to make a living, and may themselves be HIV positive.

The global health organizations and NGOs that implement donors’ programs on the ground recruit volunteers by using the language of morality. At one particular Ethiopian Volunteer Day event organized by a local NGO (HIWOT), volunteers were encouraged to sacrifice—to seek spiritual and mental rewards rather than material rewards. Themes included, “Let us protect children from HIV/AIDS and spread volunteer service” and “Everyone should give volunteer service in order to improve the country and fellow people.” In interviews with CHWs, however, Maes learned that although they work hard to fulfill the goals promoted by NGOs and their governments, CHWs also worry about caring for their own families in the context of a scarcity of electricity, water, and housing, and, perhaps most important, chronic unemployment (Maes 2017, Maes 2014, Kalofonos 2014; Swidler & Watkins 2009).

The sentiments that motivate the CHWs are both moral and instrumental: they want to do good, but they also hope that volunteering will lead to a job with an NGO, one that would improve their lives and the lives of their families.

CHW: “In all my life, what makes me happiest is to see patients being human, being able to work and feed themselves. When I see others doing good things, I say, ‘I wish to be like this person. Why doesn’t God make me the same? This is work that God likes.’” (106)

CHW: “This chair is not edible. The television and these cupboards are not edible….I got all these things previously when I was healthy—when I was working….I am stressed because I am not working, not because the virus is inside me. I also worry about how long I will rely on the support of others …What shall I do working at something [i.e. volunteering] that has no prospects for improvement…How can a woman accept me as a husband?” (106).

Maes describes the work of the CHWs in unusual detail, painting eloquent word-pictures of individual CHWs. We can almost see CHWs providing empathetic and intimate care to those with AIDS—the CHWS walk to their homes, make sure they are bathed, and check to ensure they are continuing to take their antiretroviral therapy. When a patient has no food, CHWs, on their own initiative, might go to the patient’s neighbor to ask for food to help the family. And when patients die, their CHW often prepares them for burial.

In a second description, however, Maes paints a starkly different picture, one that exposes the exploitation of the CHWs who do the work on the ground. When AIDS was declared an emergency, billions of dollars flowed from world capitals to NGOs in poor countries experiencing an AIDS epidemic. In Ethiopia, AIDS money pays not only for antiretroviral drugs that extend life, but also for supporting HIWOT—the staff members work in an office, their travel is paid, and, best of all, they receive a salary. Little of this money, however, reaches the CHWs, because the donors insist that the project be sustainable. The international doctrine of sustainability imposed by donors means that once a project ends, the volunteers are expected to continue to provide care. Although the volunteers are given a moderate amount of money during the month-long training period, after the NGO’s budget for training is spent, the staff continue to be paid but the volunteers are expected to work for free.

Ann Swidler and I have written about the many altruistic organizations and individuals who came to another poor African country, Malawi, also struck by the AIDS epidemic (Swidler & Watkins 2017). This book is a valuable addition to our understanding of the moral economy of foreign aid. We, as well as other readers, learn from Maes that the CHWs genuinely want to help their neighbors—but they also learn that the NGOs hew to the doctrine of sustainability, imposed by international donors, which dictates that the foreign aid benefits the NGOs seeking to do good far more than it benefits those who do the actual work of interacting with people living with AIDS (Swidler & Watkins 2009).

Maes’ framing of the intersection of local labor and global health is brilliant. He argues that recruiting the poorest of the poor, local, unemployed residents to make an NGO project sustainable is a problematic global health policy that in many ways is inappropriate in the settings of chronic high unemployment, poverty, and food insecurity that characterize many African countries. Maes proposes a different model, one in which volunteers are empowered not only to care for those with AIDS but also to pursue social justice and a more equal distribution of power, resources, and well-being. I agree.

Resources and Works Cited

Ferguson, James. 2015. Give a Man a Fish: Reflections on the New Politics of Distribution. Dunham and London: Duke University Press.

Kalofonos, Ippolytos. 2014. “’All they do is pray’: Community labour and the narrowing of ‘care’ during Mozambique’s HIV scale-up”. Global Public Health 9(1-2).

Maes, Kenneth. 2012. “Volunteerism or labor exploitation?: Harnessing the volunteer spirit to sustain AIDS treatment programs in urban Ethiopia”. Human Organizations 71 (1): 54-64. PMCID: PMC3783341.

Maes, Kenneth. 2014. “Volunteers are not paid because they are priceless: Community health worker capacities and values in an AIDS treatment intervention in urban Ethiopia.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 29(1): 97-115.

Maes, Kenneth. 2017. The Lives of Community Health Workers: Local Labor and Global Health in Urban Ethiopia. Anthropology and Global Public Health. New York and London: Routledge. (reviewed above)

Swidler, Ann and Susan Cotts Watkins. 2009. “’Teach a man to fish’: the doctrine of sustainability and its effects on three strata of Malawian society.” World Development 37 (7): 1182-1196. PMCID: PMC2791326.

Swidler, Ann and Susan Cotts Watkins. 2017. A Fraught Embrace: The Romance and Reality of AIDS Altruism in Africa. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

All comments will be reviewed and posted if substantive and of general interest to IAPHS readers.