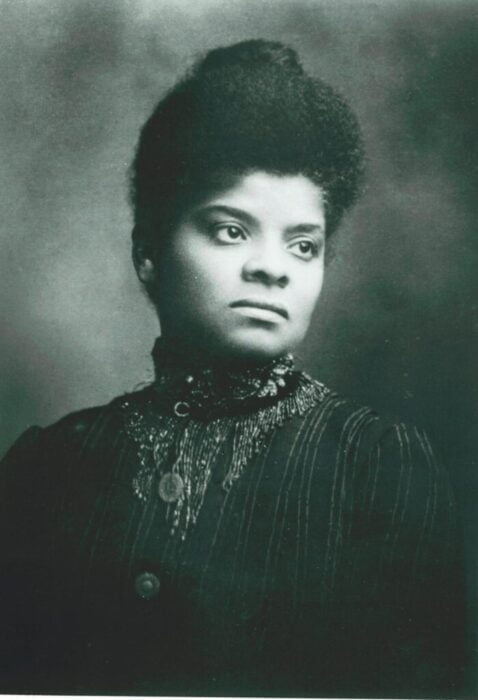

Ida B. Wells was born into slavery on July 16, 1862 in Holly Springs, Mississippi as the oldest of eight children. Her father, James, was a carpenter and her mother, Elizabeth, was a famous cook. Once slavery ended, Ida attended Shaw University (now Rust College) along with her mother who attended school long enough to learn how to read the Bible.

She was surrounded by political activists and grew up during Reconstruction with a sense of hope about the possibilities of former slaves within the American society. Both parents died, along with an infant brother, during the 1878 yellow fever epidemic when Ida was 16 years old. At that young age, she assumed the responsibility of rearing her five surviving younger brothers and sisters.

She soon became a teacher in a rural Mississippi school order to earn money for the family. After two years, she moved to Memphis for a higher paying teaching job. Although she wrote for church newspapers about inequality in many areas of life, one day changed her life forever. She was accustomed to riding the train in whatever seat she chose. In 1884, the Chesapeake, Ohio and Southwest Railroad forbade her from sitting in the ladies’ coach, even though she had a ticket. She was forcibly removed by three men because she refused to move to the colored car. She decided to sue the railroad and also wrote an article about the experience. The success of her article about the case as well as the uproar caused by her criticism of the school systems, influenced her career change from teacher to journalist. Read more

As injustices against the formerly enslaved spread throughout the South and a reign of terror began, Wells’ sense of indignation and quest for justice was fueled. Three of her male friends, who were upstanding, law-abiding, successful businessmen opened a grocery store (in direct competition with a white-owned store). They were lynched in 1892 on the pretext of a crime they did not commit. Wells decided to use her pen to expose the motives behind the violence. Her major contention that lynchings were a systematic attempt to subordinate the black community was incendiary. She wrote about the situation with a clarity and forcefulness that riveted the attention of both Black and White people. Lynching had become one of the main tactics in the strategy to terrorize Black people, and exposing its real purpose became the target of her crusade for justice. She also advocated for both an economic boycott and a mass migration of Black people from Memphis to the Oklahoma territory.

This so enraged her enemies that while she was traveling in the Northeast, they destroyed her printing press, and put a price on her head, threatening her life if she returned to the South. Despite the danger, she continued writing and speaking across the country and went to the United Kingdom to explain the brutality of lynching and the government’s refusal to intervene.

Wells was invited to Chicago by Frederick Douglass in 1893 to work on the pamphlet that was distributed at the World’s Fair to explain the lack of African American representation. In 1894, she traveled throughout England speaking about the atrocities of lynching. In 1895 she settled in Chicago when she married Ferdinand L. Barnett, a widower and a fellow crusader who was a well-known attorney as well as the founder of The Conservator newspaper. Barnett had two children from his previous marriage, the couple had four children together in eight years.

Even with this added responsibility, Wells continued in her relentless fight for social justice. She was involved with many clubs and organizations, including the National Association of Colored Women in 1896 and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909. She also was very active in the women’s suffrage movement, starting the all-black Alpha Suffrage Club in 1913. She created one of the first kindergartens for Black children in Chicago. For ten years, from 1910 – 1920, she and her husband started and ran a rooming house and social center called the Negro Fellowship League. In her final year of life, Ida ran for Illinois state senate.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett and her husband Ferdinand L. Barnett lived at 3624 S. King Drive until 1930, which is now a national landmark. Ida B. Wells-Barnett died on March 25, 1931 leaving a formidable legacy of undaunted courage and tenacity in the fight against racism and sexism in America.

She and her husband are interred at Oak Wood Cemetery in Chicago. Her legacy continues to inspire in the form of scholarships, awards, buildings, streets names, historical markers, books, movies and more.

by Michelle Duster