Stephen Bezruchka Talks Inequality, Structural Violence, and the Future of Population Health

Fred ZimmermanStephen Bezruchka has lectured and written extensively about population health in the U.S. and abroad. He is the author of the 2012 Annual Review of Public Health article, “The Hurrider I Go the Behinder I Get: The Deteriorating International Ranking of US Health Status.” Since this conversation, Dr. Bezruchka has published a piece in the Harvard Health Policy Review entitled, “Increasing Mortality and Declining Health Status in the USA: Where is Public Health?” which points out that things have gotten worse even since this interview. Dr. Bezruchka’s work has long argued that health is inherently political.

He was interviewed by Malaika Hill, principal medical writer for MD Writing and Editing Solutions.

Selected excerpts follow, lightly edited for length and clarity.

Malaika Hill: I wanted to ask you about some current issues. What are your thoughts on whether the ACA will survive, and if not what are some possible outcomes?

Stephen Bezruchka: The key thing that’s happened in the last couple of years is that our life expectancy is declining. So I think we can say that our health may have reached a peak and will start to decline. So what happened in 2014-2016 [as our life expectancy was declining]? Because of the Affordable Care Act, more people had access to healthcare. So if healthcare were doing such a great job of improving health, we wouldn’t have expected that decline. So something else is going on. I think that’s the major question that should be at the front and center focus of we as a country want to do.

Malaika Hill: I wanted to talk a little bit about the idea of structural violence. Can you elaborate on this?

Stephen Bezruchka: If we think about violence, usually the behavioral variety is one in which there’s an event that happened, there’s an outcome that is not pleasant, there’s a perpetrator—an individual—who is doing something, be it in a Las Vegas hotel with an arsenal, and the outcome is obvious: people are injured and bleeding to death and so on. That’s the behavioral variety. It is visible; there’s a perpetrator; and the outcome is obvious.

Structural violence refers also to violence—something that produces bad outcomes—but the perpetrator is not so plainly visible; there’s not a smoking gun, and you don’t die of obvious trauma. That is, there’s no gunshot wound, collision with a vehicle, or something whose effect is obvious.

I call this the highly toxic gas of inequality. It’s odorless, colorless, invisible. It kills us from the usual conditions we die of, and we’re totally unaware of it. –Stephen Bezruchka

So the economic and political structure of society—the way it cares and shares, the way it addresses early life—those are made by political choices. Take the example of our health decline. It’s not because of a shooter in some hotel. It’s also not because of the so-called opioid epidemic, although that’s a part of it. It’s caused by the way we have decided to take the recently passed tax reform that’s going to give all sorts of benefits to the rich. No question the rich will get richer. So if the relationship between more inequality and worse health is preserved—and all the evidence points to that—we can expect to see more deaths. We will see them from the usual conditions that kill us—cardiovascular disease, cancers—and there’s no smoking gun. There’s nobody pulling the trigger. And we don’t blame anybody.

I call this the highly toxic gas of inequality. It’s odorless, colorless, invisible. It kills us from the usual conditions we die of, and we’re totally unaware of it.

Malaika Hill: Do you think the inequality also harms the wealthy and powerful and not just people in the lower income bracket?

Stephen Bezruchka: That’s a very good question, and the answer is yes according to the available studies. The richer people, the studies indicate, would be healthier if they were less rich in a more equal society.

Take the 2013 Institute of Medicine report, “U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health.” I always tell my students, craft a title that says everything. And that’s a brilliant title. On p. 3 they write that those of us who are upper-income, college-educated, have white skin, practice all the best behaviors and access medical care appear to be in worse health than similar groups in comparison countries.

The richer people, the studies indicate, would be healthier if they were less rich in a more equal society. — Stephen Bezruchka

Malaika Hill: Can you share your views on the future of population health?

Stephen Bezruchka: The concept, the phrase came into use in the 1980s. I think it was coined by Fraser Mustard in Canada in about 1986 or 7. They were trying to find a new word to describe what they understood as distinct from health care and as distinct from public health. And public health is, you know, in this country, telling people to not smoke, to get their shots, wear their seatbelt and provide healthcare services for some low-income people and so on. It’s a circumscribed set of interventions supposedly to improve the health of the public but clearly it’s not doing that. And medical care is a relatively minor player. So population health was to look at the factors that actually produced health in populations

Now the phrase has been co-opted by many. There are schools of population health in the United States, departments of population health, there are hospital corporations whose tagline is population health. So the term is used variously by people and I think it is straying from its original intent to consider the broadest categories of what makes a population healthy.

One of the key factors that led me to think of factors that affect populations that are different than what individuals do to produce health came when I discovered that the longest-lived country in the world, Japan, is also the rich country with the highest proportion of men smoking. More than twice as many men smoke in Japan as in the United States. For men who smoke in Japan it appears that smoking doesn’t affect their health as much as it does for men in the United States. So I came to realize that the context in which you do a behavior, such as smoking, seems to affect the outcomes that that behavior produces.

Healthy societies have somehow structured conditions so that people are more likely to be healthy. And most of this has to do with spending or addressing social factors, in other words, what a society does to take care of its people. Does a society have a lot of poverty, do they have a lot of teen births, do they have a lot of homelessness. These are all decisions made on how we structure our society.

Malaika Hill: Finally, I wanted to get your suggestions for improving our health in the near term and in the long term.

Stephen Bezruchka: Important question. The IOM report that I mentioned, when they came to [the section on] what to do, they said, number one: inform the people. The public has to know that our health status is not good compared to other countries.

Then the other advice in the Institute of Medicine’s report was to look at healthier countries to see what they’re doing that could be of use here. Healthier countries have various policies in place to create a healthy life. One of the policies is giving parents the time and resources to parent. There are only 2 countries in the world in which a pregnant woman is pregnant and then has a baby does not have paid time off work to work: the United States and Papua New Guinea. Studies show that most people throughout the country believe we should have a paid parental leave law.

We have the most child poverty of any rich country, according to UNICEF. Actually, that’s not quite true if you count Romania as a rich country. We could do something about it, except we have this belief that the poor are poor because of something they did, and they just have pull themselves up by their bootstraps. The evidence is not very strong for that.

Malaika Hill: I think the readers will really be interested in this talk. Did you have anything else you felt was important to discuss around this topic?

Stephen Bezruchka: When I began my career as a doctor in the 1970s, I thought maybe it was medical care that made a population healthy. By the late 1980s I couldn’t explain why U.S. health was falling behind so many other countries, and I came to see that it’s political and economic and social policies that matter to produce health. The idea that health is a political construct is mostly missing from any discussion.

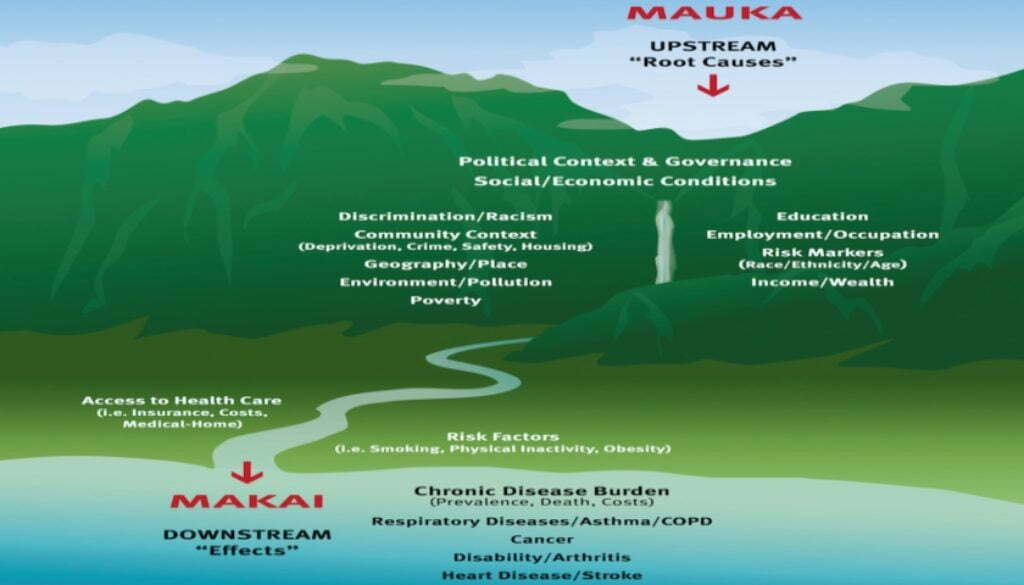

But not always. The Department of Health in Hawaii—and Hawaii is one of our healthiest states—issued a report in 2011 in which they had a graphic: Upstream and Downstream. Upstream are root causes. The number one is political context and governance. That’s remarkable for a state health department to make such a statement—I mean the data all point to it.

To do something, we have to do something that’s political, and we have to address early life. And the political thing we need to do is decrease the gap between the rich and the poor. And the early life thing: we need to care for mothers and family and children.

One other thing I didn’t mention. Racism has an additive effect to everything else I’ve mentioned. So that always has to be at the table.

Malaika Hill: Thank you so much. It was great talking to you and I learned so much.

Stephen Bezruchka: Well, thank you for asking good questions. By the way, there’s another quote that I like from Thomas Pynchon, “If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don’t have to worry about the answers.”

December 16, 2018 @ 6:09 pm

From here Bezruchka compares this number of dead to the September h attacks (one would need to occur every four days to keep pace), and introduces my favorite phrase: structural violence. He gives personal examples of poor outcomes that needn t be; examples not from his medical practice, but just people he knows. His sister-in-law bleeding to death on an operating table from a cancer surgery. Had she not had the surgery, she would likely still be here today. His next door neighbor having liver surgery in a top-ten hospital and also dying in a similar situation.

December 16, 2018 @ 9:22 am

Stephen Bezruchka opens his talk with an analogy about a town on the coast, with great hot springs that attract many tourists. The road leading to the town affords a breathtaking view, but comes perilously close to the edge of some cliffs before turning left into town occasionally cars plummet over the edge. Enough cars begin to fall over the edge that the town leaders get together and hire experts and consultants to figure out what can be done. After studies and analysis, the answer is found, and the town leaders announce they will build a state-of-the-art trauma center at the bottom of the cliff.