When it Comes to Systemic Racism in Policing, Don’t be Fooled by Flawed Statistical Reasoning

Susan Mason, Dunia Dadi, Richard MacLehose, Steven Stovitz, Jay KaufmanThe murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 25th has renewed the public’s focus on disproportionate police violence against Black people, particularly Black men. A Black man has a one in a thousand chance of being killed by a police officer, a risk more than three times that of his White neighbors. In Minneapolis, the police are seven times more likely to use force against a Black person than against a White person. These stark and urgent disparities are just the tip of an iceberg of trauma related to police mistreatment that has been experienced by many communities of color.

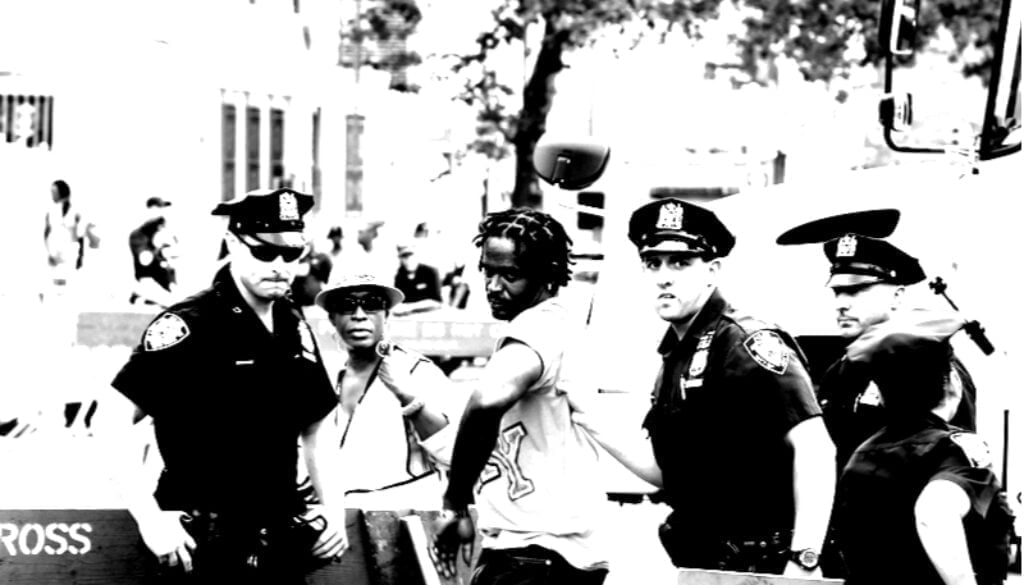

The murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 25th has renewed the public’s focus on disproportionate police violence against Black people, particularly Black men. A Black man has a one in a thousand chance of being killed by a police officer, a risk more than three times that of his White neighbors. In Minneapolis, the police are seven times more likely to use force against a Black person than against a White person. These stark and urgent disparities are just the tip of an iceberg of trauma related to police mistreatment experienced by many communities of color.

Yet, in the face of these ongoing human rights abuses, there are some who argue that there is no systemic racism in policing. These authors cherry-pick statistics: for example, reporting the larger raw number of White people killed by police, without accounting for the much larger White population. More insidiously, some authors arrive at a conclusion of no police racism through the appearance of sophisticated statistical analyses. These studies restrict their analyses to those who have had encounters with police, claiming to control for factors such as criminal activity, and then conclude that Black people are no more likely–and in some cases less likely–to be shot by the police than White people are.

What should we make of the paradox between these “no police racism” findings and the plain fact that Black people are far more likely to be shot and killed by police than White people are? Do these findings mean these researchers have successfully controlled for “criminality” in their studies? As epidemiologists, we think that the opposite is true: restricting analyses to individuals who have had a police encounter has actually created a statistical bias that our field calls “collider stratification bias.” This type of bias is notorious for making things that are truly harmful look innocuous or even beneficial. There is a large and technical body of literature on this topic, but the upshot: when you restrict your sample to those who have had a police encounter, you by definition include only those people who had some reason to have a police encounter. If the reasons for an encounter are systematically different for Black people than for White people, a comparison of Black people to White people in police encounters is not a comparison of people who differ only by the color of their skin.

To see why this is a problem, let us imagine a simplified scenario. Suppose that the two main reasons that an individual is confronted by the police are either that they are (a) engaging in a crime or (b) Black. Stopping people for reason “a” is, of course, the mandate of our police forces. We know that reason “b” also happens, owing to policies that encourage racial profiling without evidence of a crime, disproportionate police presence in Black neighborhoods, and explicit or implicit bias on the part of individual officers. In this scenario, all Whites in police encounters must have engaged in a crime, whereas Blacks could have either engaged in a crime or not. Though the real world is not as simple as this example, we do know that a smaller proportion of police stops of Black individuals result in evidence of a crime than do stops of White individuals. Because stops associated with actual evidence of a crime are inherently more likely to escalate to the use of force, we would expect to see more violence in these encounters, which are disproportionately encounters with White people.

Some studies claim to account for imbalances in the reasons for police encounters with Black versus White individuals. However, this accounting requires police to accurately report reasons for the encounter. Recent events have exposed the extent to which the accuracy of police reports is questionable. Even when police officers are not being willfully misleading, we know that implicit bias leads individuals to perceive Black people as more threatening than White people, independent of their behavior.

In short, the findings that, among those in police encounters, Black people are equally or less likely than White people to be shot are far from evidence against racism in policing. Such a conclusion relies on flawed statistical reasoning. In fact, these findings are the predictable product of a racist police system that stops and detains masses of average Black individuals who pose little risk, with no similar targeting of White people. The statistics are clear that Black people bear the brunt of police violence. The question is whether there is finally political will to remedy this injustice.

All comments will be reviewed and posted if substantive and of general interest to IAPHS readers.