Understanding Multilevel Barriers to Healthcare for Transgender Populations in the U.S.

Jackie White HughtoTransgender people–people who have a gender identity that differs from their assigned sex at birth–experience widespread stigma in the United States. Stigma impacts transgender people’s access to essential resources, including employment, housing, and healthcare. (1) In a large national study, 28% of transgender people reported verbal harassment in healthcare settings, and 19% reported being refused healthcare in their lifetime. (2) While healthcare access in the general population is known to differ according to individual characteristics like gender identity, as well as according to geographic location and local characteristics, few studies have sought to simultaneously explore multilevel risk factors for being refused healthcare refusal among transgender populations.

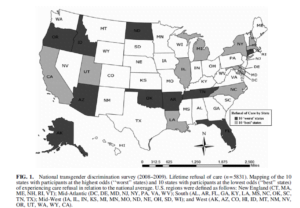

In a recent study published in LGBT Health, my collaborators and I combined a data set from a large national survey of transgender adults 2 with national, population-based data (e.g., census data, election results by state, state-level policies) (3-5) to identify individual and geographic factors that are positively associated with experiencing healthcare refusal. We documented variation in healthcare refusal across US states, with those residing in the Southern (i.e., Arkansas, Florida, Oklahoma, Tennessee) and Western (i.e., Arizona Alaska, Idaho, Oregon) US at increased odds of having been denied care, relative to residents in other regions of the U.S.

Healthcare refusal was assessed across participants’ lifetimes in this study, so experiences of refusal could have happened recently or some time ago. Still, many states in the Southern or Western U.S. have been slower to enact transgender non-discrimination policies, relative to most states in New England. (6-8) While many Western states now have policies that protect against discrimination in public accommodation settings, including in healthcare, protective policies are only effective when enforced. Further, protective transgender policies still remain absent in Southern states.(7) Thus, more work is needed to identify the state-level barriers, such as social, political, and economic factors, that may be contributing to the geographic variability in healthcare refusal among transgender adults, including the impact of policy creation and enforcement on healthcare access for this population.

Our study also found that the percent of residents voting Republican was the strongest state-level indicator of healthcare refusal. Research demonstrates that political affiliation and voting behavior often serve as proxies for local attitudes and culture towards a range of topics, from gun ownership to immigration or religious freedoms. (9) Prior research has found that Republican-identified voters are more likely to hold homophobic attitudes and fears of AIDS than are Democratic-identified voters. (10-12) If Republican voters are also more likely to hold transphobic attitudes then Democratic voters are, transgender individuals in states with majority Republican voters might be more likely to encounter biased providers and, therefore, be more likely to be refused care then transgender individuals living in states with a Democratic majority. Additional research is necessary to explore the mechanisms through which state-level voting practices are associated with access to care for transgender people.

Several key demographic and behavioral factors among participants in the study were also found to be associated with having been refused care Transgender participants with higher incomes were significantly less like to report being refused care than those with lower incomes; higher income transgender individuals may be able to travel further to find supportive healthcare services. (1) Other research also finds that transgender people who demonstrate an ability to pay are treated better in healthcare encounters than are individuals who cannot afford to pay. (13,14) Thus, the heightened prevalence of care refusal among people with low incomes may be at least partially related to bias based on a patient’s income.

Additionally, we found that avoidance of healthcare due to fear of mistreatment was associated with having been refused healthcare in the past. Given previous research showing that stigmatized individuals (e.g., those who were refused care) nervously anticipate, routinely observe, and anxiously react to rejection 15, and are thus more likely to (e.g., they avoid healthcare), therapeutic intervention strategies are needed to address the cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to stigma among transgender people. Educational interventions that aim to reduce transgender stigma among healthcare providers, as well as the creation and enforcement of transgender non-discrimination policies, are also needed to curb transgender stigma at its source. Together these intervention efforts can help ensure access to healthcare and safeguard the health of transgender people across the US.

Overall, our study highlights the role that both individual and geographic factors play in understanding healthcare access for transgender populations in the U.S. In addition to better characterizing the many factors that shape healthcare access, our findings pave the way for targeted, multilevel interventions to overcome barriers to care, particularly for transgender individuals living in regions where they are at particular risk for healthcare refusal.

References

- White Hughto JM, Reisner SL, Pachankis JE. Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2015;147:222–231.

- Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis LA, Harrison J, Herman JL, Keisling M. Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force;2011.

- Federal Election Commission. Federal Elections 2008: Election Results for the U.S. President, the U.S. Senate, and the U.S. House of Representatives. http://www.fec.gov/pubrec/fe2008/federalelections2008.shtml. Accessed June 19, 2016.

- The Pell Institute. Gini Coefficients for Family and Household Income by State, 2008. http://www.pellinstitute.org/. Accessed June 19, 2016.

- United States Census. Same-Sex Couple Household Statistics from the 2010 Census. http://www.census.gov/hhes/samesex/data/decennial.html. Accessed June 19, 2016.

- Transgender Law and Policy Institute. U.S. jurisdictions with laws prohibiting discrimination on the basis of gender identity or expression. 2012; http://www.transgenderlaw.org/ndlaws/.

- Transgender Law Center. Non-Discrimination Laws: Public Accomodations Map. National Equity Map http://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/non_discrimination_laws?iframe=full. Accessed June 28, 2016.

- National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Scope of Explicitly Transgender-Inclusive Anti-Discrimination Laws. Transgender Law and Policy Institute;2008.

- Kimmel MS, Mahler M. Adolescent masculinity, homophobia, and violence random school shootings, 1982-2001. Am Behav Sci. 2003;46(10):1439-1458.

- Morrison MA, Morrison TG. Development and validation of a scale measuring modern prejudice toward gay men and lesbian women. J Homosex. 2003;43(2):15-37.

- Oswald RF, Culton LS. Under the rainbow: Rural gay life and its relevance for family providers. Fam Relat. 2003;52(1):72-81.

- Walch SE, Orlosky PM, Sinkkanen KA, Stevens HR. Demographic and social factors associated with homophobia and fear of AIDS in a community sample. J Homosex. 2010;57(2):310-324.

- Dewey JM. Knowledge legitimacy: How trans-patient behavior supports and challenges current medical knowledge. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(10):1345-1355.

- Gehi PS, Arkles G. Unraveling injustice: Race and class impact of Medicaid exclusions of transition-related health care for transgender people. Sex Res Social Policy. 2007;4(4):7-35.

- Mendoza-Denton R, Downey G, Purdie VJ, Davis A, Pietrzak J. Sensitivity to status-based rejection: Implications for African American students’ college experience. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;83(4):896-918.

All comments will be reviewed and posted if substantive and of general interest to IAPHS readers.