U.S. Health Policy and Population Health: Where We Are Now and Where We’re Headed

Tiffany JosephPassed in 2010 under former President Barack Obama, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), also known as Obamacare, was a historic achievement expected to increase health insurance access for Americans. It was resisted by Republican politicians and underwent two Supreme Court Challenges before and during implementation. These factors yielded an imperfect implementation, with politically blue states generally opting in and red states often opting out. Nonetheless, ACA reduced the nation’s uninsurance rate to 9 percent and increased coverage for nearly 28 million Americans via the Medicaid expansion and marketplace exchanges by the end of 2016 (KFF 2016; ObamacareFacts.com 2016). Young adults up to age 26 could also remain on their parent’s plans, which increased coverage for a group at risk of being uninsured.

Separate and not equal

However, the ACA’s “success” was not equally felt by everyone (Joseph 2017). Nineteen states opted out of the Medicaid expansion, which excluded low-income Americans in those states. Most immigrants were also ineligible for Medicaid, meaning that up to 13 percent of the population has remained excluded by law from Obamacare (Joseph 2017).

What does this mean for population health? Studies of Obamacare studies reveal a growing divide in health care coverage and access more concretely tied to income level, documentation status, and state of residence. An estimated 3.1 million uninsured low-income individuals and eligible long-term legal permanent residents or citizens in opt-out states could have benefited from the Medicaid expansion, but did not (Artiga et al. 2015). Eighty-nine percent of these individuals live in Southern states, which have the nation’s worst health outcomes (Artiga and Damico 2016; Garfield and Damico 2016).

Because many immigrants and potential Medicaid expansion beneficiaries in opt-out states are low-income and people of color, ACA successes are further tempered along class, racial, and ethnic lines. Twenty-seven percent of Latino adults and 16 percent of black adults remain uninsured compared to 13 percent of “other” people of color and 11 percent of whites (Artiga et al. 2015). Healthcare access stratification under the ACA likely means that certain disparities will persist, particularly for socially disadvantaged populations (Castañeda 2017; Flores and Vargas 2017; Joseph and Marrow 2017; Sanchez et al. 2017).

Repeal and replace

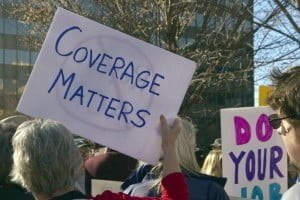

But health care stratification would certainly worsen without the ACA (Aron-Dine and Straw 2017; Blumenthal and Collins 2017; Park, Solomon, and Katch 2017). While former President Obama and other ACA supporters acknowledge that the policy can be improved, rivals of the law want to “repeal and replace Obamacare.” This was a central tenet of Trump’s presidential campaign, and GOP lawmakers have been drafting such legislation since President Trump’s inauguration.

Since March 2017, there have been numerous unsuccessful attempts to repeal and replace Obamacare in the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate. The proposed bills aimed to: (1) end Medicaid expansion funding; (2) remove the individual and employer mandates; (3) strip essential benefits and pre-existing conditions from coverage policies, (4) provide age-based tax credits for middle-income and older Americans to purchase insurance in the exchanges; and (5) redistribute tax credits from lower and middle-income to wealthier Americans (Aron-Dine and Straw 2017; Cox, Claxton, and Levitt 2017; Jacobson 2017; Park and Andrews 2017). The Congressional Budget Office estimated that these bills would eventually reduce the federal deficit by as much as $337 million at the expense of 22 to 32 million Americans becoming uninsured (Blumenthal and Collins 2017; CBO 2017a,b; Pear and Kaplan 2017a; Park 2017).

Since March 2017, there have been numerous unsuccessful attempts to repeal and replace Obamacare in the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate. The proposed bills aimed to: (1) end Medicaid expansion funding; (2) remove the individual and employer mandates; (3) strip essential benefits and pre-existing conditions from coverage policies, (4) provide age-based tax credits for middle-income and older Americans to purchase insurance in the exchanges; and (5) redistribute tax credits from lower and middle-income to wealthier Americans (Aron-Dine and Straw 2017; Cox, Claxton, and Levitt 2017; Jacobson 2017; Park and Andrews 2017). The Congressional Budget Office estimated that these bills would eventually reduce the federal deficit by as much as $337 million at the expense of 22 to 32 million Americans becoming uninsured (Blumenthal and Collins 2017; CBO 2017a,b; Pear and Kaplan 2017a; Park 2017).

Given the House and Senate’s inability to muster enough support for their proposed bills, the ACA will remain the law of the land for the foreseeable future. However, the Obamacare repeal threat has made current and potential beneficiaries wary of (re)enrolling. These repeal attempts, along with threats to end cost-sharing payments and other under-the-radar methods, have also generated uncertainty in the health insurance market, making insurance companies reluctant to issue policies in certain states or to participate in health exchanges (Ellis 2017; Rosenbaum et al. 2017). Consequently, ACA enrollees have fewer and less comprehensive coverage policies from which to choose.

Population health research opportunities

While the ACA remains in place, it is imperative that population health scientists continue to study the policy’s impacts on shaping healthcare access, use of health services, and a range of physical and mental health outcomes.

Population health scientists have yet to fully understand how race and ethnicity, along with documentation status, present challenges for some groups of Americans trying to navigate the healthcare system. Amid increasing anti-immigrant sentiment and racist behavior, hate crimes and discrimination against citizens and immigrants of color have increased since President Trump’s inauguration. These factors certainly shape one’s decision to obtain health care. But implicit biases towards these groups in the healthcare system might also deter them from seeking care, even if they have ACA coverage. Such discrimination may also affect these groups’ overall health, increasing ethno-racial health disparities.

It will also be critical to better understand how the state and even the neighborhood where people live affect health coverage and outcomes. Research has shown that one’s zip code matters, and that living in an ACA opt-in state may improve one’s health outcomes (Garfield and Damico 2016). The ACA provides a unique opportunity for population health scientists to understand how macro-level policies affects individuals at the micro-level. Thus, together with pre-ACA population health research, population health scientists can provide evidence of Obamacare’s impact and also set a comparative mark for how population health could be affected in the ACA era. In doing so, population health scientists will need to convey their findings to audiences beyond fellow researchers – to the general public and lawmakers – to sound the alarm about the ongoing and worsening stratification in the American healthcare system.

Additional Reading

Tiffany D. Joseph and Helen B. Marrow. 2017. “Health Care, Immigrants and Minorities: Lessons from the Affordable Care Act in the United States.” Special Issue of the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Co-guest Editors, published online June 12.

All comments will be reviewed and posted if substantive and of general interest to IAPHS readers.