Learning from Slum Upgrading for Building Healthy Communities: An Interview with Jason Corburn

Kristin HarperRecently, UC Berkeley Professor Jason Corburn was awarded an 18-month grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for his project “Learning from Slum Upgrading for Building Healthy Communities.” Here, we interview him about his planned work.

What is the goal of this project?

The idea is to initiate a set of conversations between activists, researchers, and decision-makers involved in building more healthy and equitable communities. We hope to share strategies and learn from one another across the Global South and North, with the ultimate goal to reduce social and health inequities in urban communities around the world. Participants in the project include community activists, researchers, NGOs, community-based organizations, and community residents. The goal is to have practitioners from countries in the Global South, mostly in Africa and Southeast Asia, engage in a deep conversation with healthy community activists and practitioners in low-income communities of color in the U.S, namely in East Oakland and Richmond, California. This is just a starting point. The idea is not to rush to find one best practice, but to develop a new global network of practice – of action – that supports health equity.

How do you plan to implement these ideas?

The first task is creating a “global healthy-community learning infrastructure” where our partners share strategies, experiences, challenges, and cultural norms. To facilitate this, a few weeks ago, we brought some of the East Oakland partners to Kenya for two weeks where they met with activists from Nigeria and Kenya. We visited community-based projects and held intensive dialogues on mobilization, action-research, and policy engagement, and even watched the documentary 13th to discuss the parallels between colonialism and structural racism in the U.S. The goal was to gain understandings about the health, economic. and community development challenges facing communities in different cultural and political contexts.

The next step is to bring people living in slum areas from Africa and India to the San Francisco Bay Area for a workshop with East Oakland and Richmond practitioners. The first workshop is really about sharing and getting to know each other. Understanding the challenges of maintaining a healthy community in each place. UC Berkeley will act as an intermediary, organizing pre-conference materials, documenting findings, and preparing a follow-up workshop focused on moving from understanding to action, in both the U.S. and developing countries.

The second workshop will focus on how we can develop one or two interventions together; now that we know about each other, what might we help one another to do, or to do better? We expect that the U.S. participants will learn from the African and Asian practitioners some strategies that might extend or enhance their approach to urban betterment, and vice versa. The idea is that the plan for these interventions would be co-created during the grant period, but implemented with additional resources later in 2018 and beyond. Since UC Berkeley is already working on action-research projects with many of the partners – including those in Africa, Oakland and Richmond – we are committed to continuing to support and expand the network as well as conduct the interventions.

How did you get interested in slum upgrading?

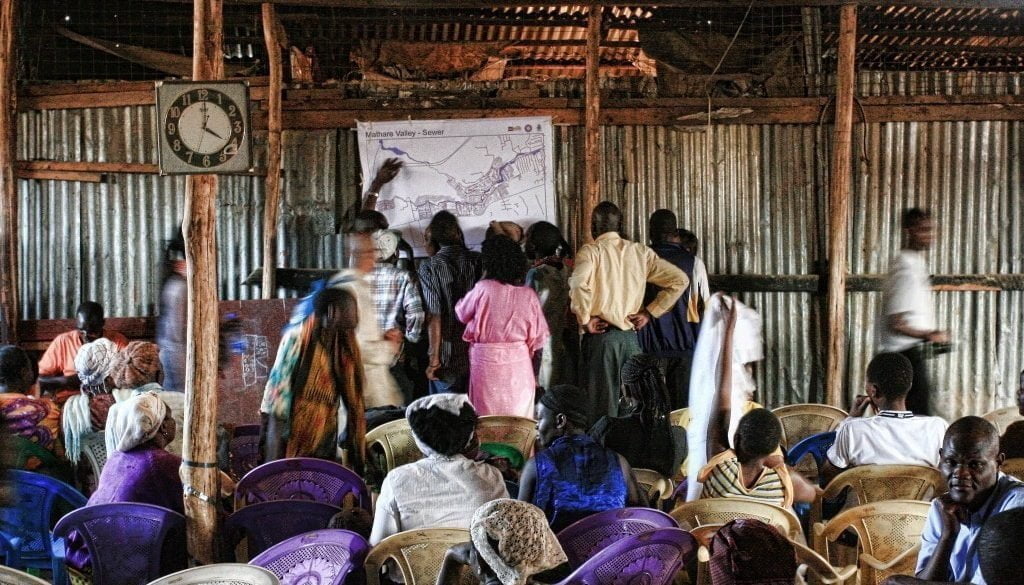

I’ve been working in this area for at least a decade, in partnership with a global organization called Shack/Slum Dwellers International, or SDI. My role has been to give technical assistance, and conduct community-based action research and impact evaluations with them, particularly with partners in Kenya. In 2008, a group of SDI community partners approached me to support them in preventing evictions planned for slum dwellers in the Mathare community of Nairobi. We developed a strategy with residents, a local organization called Muungano wa Wanavijiji (Swahili for “the federation of the urban poor”), and the University of Nairobi to map and document who would be displaced. This allowed us to quantify the number of people, businesses, services, and other things that would be displaced, and to estimate the health impacts, not only on this community of over 200,000 people, but for the entire city. We were successful in stopping the evictions.

We have built on that collaboration over the past decade to use action-research with our partners to do other projects that improve population health in the areas of housing and infrastructure, and we have helped to draft policies and to negotiate with international organizations for more accountable investments. Remember, many of these communities are still “invisible” to those in power – from the perspective of the powerful, these communities don’t, or shouldn’t, exist. They’re informal. So, if you don’t “officially” exist, you don’t get basic life-supporting services. Part of our role is to support local people and organizations to help make them and their issues visible, often via data collection, surveying, and mapping. This is a key piece of the healthy community building strategy.

Where did the idea for these exchanges between practitioners come from?

We have been co-leading an exchange of our students and faculty with our Kenyan partners since 2009. We’ve also brought Kenyan faculty, students, and NGO partners to Berkeley. In addition, a key aspect of the SDI model of community change is what they call South-South exchanges, where they’ll have a team of community leaders from their network visit community organizations in another city, such as members from Lagos visiting Nairobi, or those from Kampala visiting Mumbai. The teams exchange strategies, see projects and meet with residents in the communities, and even meet with local government officials. So, we are building on these previous efforts, but expanding to include more U.S.-based organizations and issues.

What are some of the biggest differences in practices between the U.S. and the Global South?

Clearly, the role, power, and resources of the state differ widely between the U.S. and in cities of the Global South. Yet, there are many similarities; in both places, we focus on communities that have been ignored and divested from, that exist largely outside the formal economy, and are segregated from the other benefits of city living. This means that much of the work is self-help, while at the same time trying to change structural conditions that contribute to persistent inequalities.

One difference in practice between the U.S. and the Global South is that the SDI groups focus on something called microsavings. In this practice, community-based organizations act as mini-banks, helping their members save small amounts, like pennies a day. This not only builds financial capital but also social capital. That small amount of financial capital winds up being an important social safety net. For example, suppose somebody needs a cesarian-section, but they don’t have the money. A small savings group actually can use that pooled money to help one of their members. At the same time, the organization brings these “invested” people together to do the survey research, mapping, project, and policy work to change living conditions.

If we think about the key determinants of health, the key driving factors are poverty, a lack of wealth creation, an intergenerational lack of economic mobility, and access to political power. We’ve known that for a century or more. The question is: are there variations of strategies, like microsavings, that have proven successful in the Global South that can be applied in places like East Oakland, Richmond, and other U.S. urban communities that face persistent poverty, discrimination, and racial segregation? And can this be one strategy among many to improve their well-being?

Are there any thoughts you would like to leave our readers with?

There hasn’t been a lot of South-North learning in community health. Conventional approaches have been more along the lines of, “We’re the rich, smart, experienced United States. We know how to do things well.” The reality is, we still have too many health inequalities that persist along the lines of poverty, race, and ethnicity. We can’t continue down the same paths in public health, urban planning, policy, or even community social movements, and expect different outcomes. Efforts to upgrade slum conditions in the Global South show us that communities can be radically transformed for the better, even in the context of limited governmental willingness and investment resources.

I believe population health work needs to take a closer look at some of the innovations in the Global South to re-think and expand the work here in the U.S. Building more healthy and equitable communities in the United States is going to require new strategies, new priorities, new partnerships, and a different kind of engagement with researchers and communities. That’s what we hope to foster with these exchanges.

Want to learn more about this work?

A web site will be launched soon, but for now you can visit The Center for Global Healthy Cities, The Institute of Urban and Regional Development, and my website.

Bio: Jason Corburn is a Professor at the University of California, Berkeley in the Department of City & Regional Planning and the School of Public Health. He directs Berkeley’s Institute of Urban and Regional Development and leads the Center for Global Health Cities.

Bio: Jason Corburn is a Professor at the University of California, Berkeley in the Department of City & Regional Planning and the School of Public Health. He directs Berkeley’s Institute of Urban and Regional Development and leads the Center for Global Health Cities.

June 12, 2018 @ 3:20 am

We are lucky if we have all the comforts in life, but are we all familiar with the millions of people who have no shelter and are struggling for food every day. They are helpless and are forced to lead a miserable life. Also agree with your information, there are a number of NGO’s like http://www.mission-humanitaire-afrique.org that work day and night for the benefit of needy but that would not be enough as the count of people facing poverty is large, so we should come together and be a helping hand for all needy.