Implementing a Population Health Program in a Community Health Center

Benjamin Oldfield, Lori Reynolds, Amanda DeCewJack Geiger, a foundational figure in the American community health center movement, made clear from the outset that the health centers he envisioned would unite primary care and population health strategies. “We [will] use the principles of community-oriented primary care and population health,” he recalled being said at a planning meeting in 1964, “to deliver services and, although we didn’t use the words at the time, address the social determinants of health.”

Over a half century later, community health centers (CHCs) across the nation now care for more than 27 million Americans. They formalize patient engagement by requiring a governing board of at least 51% patients, and CHCs mandate the public reporting of clinical, operational, and financial metrics. In community-engaged efforts that are increasingly data driven, therefore, today’s CHCs are ideally situated to actualize Geiger’s vision and be trailblazers in population health science and implementation.

At our CHC—Fair Haven Community Health Care, in New Haven, CT—we formally launched a population health program in July 2018 to improve the health of our approximately 18,000 patients, most of whom receive state-sponsored insurance and about a quarter of whom are uninsured. Spearheaded by a Medical Director of Population Health (Ben Oldfield) and a Nursing Coordinator (Lori Reynolds), our work is grounded by four foundational principles that draw on prior work of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and were refined by an interprofessional group of clinicians and leadership at our CHC. Here, we describe each principle and illustrate with example projects.

1.Improving the health of defined populations

Kindig and Stoddart defined population health as “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group.” Reporting quality metrics to federal funders obligates that CHCs study patient groups according to this framework. At our organization, diabetes mellitus is disproportionately prevalent (20%, versus a national prevalence of 9%) as is prediabetes mellitus (40%, versus a national prevalence of 34%), likely reflecting unequal distributions of resources that impact patients’ ability to achieve healthy lifestyles, trust providers, and engage in preventive care and/or treatment.

Building on our prior work that established a successful Diabetes Prevention Program, we constructed a diabetes clinic one half-day per week. We staff the clinic with a family medicine provider, nurse, and care coordinator to target those with poorly controlled diabetes to re-engage them in care and address the overlapping biological and social drivers of their disease. Similar population-specific programming exists for children with developmental disorders and adolescents in need health maintenance visits. Tracking the outcomes of our efforts by race, ethnicity, gender, age, and insurance status allows us to modify programming iteratively to ensure that we are promoting health equity among measurable subpopulations.

2. Addressing social and structural determinants of health

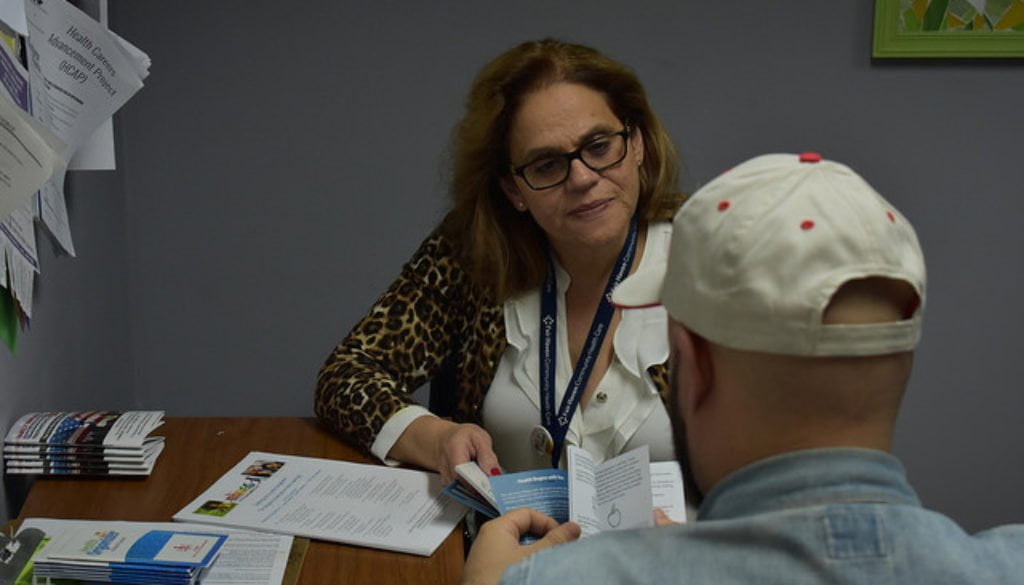

The impact of social and structural determinants—the conditions, policy milieu, and social hierarchies in which people live and work—on the burden of disease are increasingly recognized as important. Operationalizing them into clinical workflows can be complex. Using the screening instrument of the Accountable Health Communities Model of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, our care coordinators screen patients for housing insecurity, environmentally compromised housing, food insecurity, transportation difficulty, interpersonal violence, economic difficulty, and social support. In patients’ electronic medical records, care coordinators add diagnoses to the problem lists that correspond to positive screens, and then mobilize area resources to mitigate the needs identified. Once on problem lists, these needs are trackable, facilitating inquiry into their association with medical comorbidities, clinical outcomes, and geographic location to inform outreach and advocacy efforts. They can also be layered onto predictive models of health services utilization and cost.

The impact of social and structural determinants—the conditions, policy milieu, and social hierarchies in which people live and work—on the burden of disease are increasingly recognized as important. Operationalizing them into clinical workflows can be complex. Using the screening instrument of the Accountable Health Communities Model of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, our care coordinators screen patients for housing insecurity, environmentally compromised housing, food insecurity, transportation difficulty, interpersonal violence, economic difficulty, and social support. In patients’ electronic medical records, care coordinators add diagnoses to the problem lists that correspond to positive screens, and then mobilize area resources to mitigate the needs identified. Once on problem lists, these needs are trackable, facilitating inquiry into their association with medical comorbidities, clinical outcomes, and geographic location to inform outreach and advocacy efforts. They can also be layered onto predictive models of health services utilization and cost.

3. Building community capacity

A focus on social determinants obligates that we look outside our CHC walls to remove barriers our patients face in achieving good health. Asthma impacts our area disproportionately, a disparity driven partly by poor housing stock. Funded by the Connecticut State Innovation Model, we are partnering with a local health department’s community health worker program to improve the self-management and living situations of families with persistent asthma. In so doing, we are addressing the needs of families while generating local opportunities to advocate for improved housing.

4. Empowering clinical teams to drive population health management

Workflows to close gaps in care are piloted by the Medical Director of Population Health and the Nursing Coordinator, but they don’t stop there. Once electronic medical record-based reports identifying those in need are constructed, and processes for patient re-engagement are trialed, we empower clinical teams (typically a provider, nurse, and clinical assistant) to take over and apply workflows to their own panel of patients. This transformation of clinical duties, which can take as little as a half-hour per week of panel management per clinical team, is worthwhile for both population health and staff well-being. Empowering clinical staff by broadening their impact on clinical care and diversifying their workload may increase workplace satisfaction.

CHCs are ideal hubs for population health efforts because of their focus on health care access, quality, and cost containment. Furthermore, their historical knowledge and engagement of marginalized populations enables their efforts to reach those who may need them the most. Acting upon the principles outlined above is not only central to the vision offered by Geiger years ago, but will also expand a delivery model that promotes equity and improved health of vulnerable populations across the country.

Advice for other CHCs interest in population health

As we have done, other CHCs can start formalizing their population health efforts by building an interdisciplinary team that draws from from previously successful programming. Establishing an agreed-upon set of principles of population health can help organize efforts and engage stakeholders. In partnership with information technologists, teams can identify gaps in access, care, and care quality. Then, identifying the organizational levers (such as quality improvement or better-value care) and the environmental levers (such as related efforts by community-based organizations and local policy initiatives), teams can harness the strengths of their organization’s inner and outer climates towards mitigating those gaps, improving the health of the population.

All comments will be reviewed and posted if substantive and of general interest to IAPHS readers.