Echoes of Historical Racism in the ACA’s Exclusion of Unqualified Immigrants

Melanie TerrasseRhetoric and policies throughout 2017 rekindled a debate about immigrant rights and integration in the United States. Initiatives such as the immigration–or “travel”–ban and the debate over DACA, along with the attempted repeal of the Affordable Care Act, all point to a contraction of rights and access for racial and ethnic minorities. The recently published theoretical and historical analysis by Donald Light and me shows how the legacy of post-Civil War Southern racism continued to shape unequal health access for racial minorities and immigrants, from the creation of the first national public health programs to the Affordable Care Act itself. The recent attempt to reform U.S. health care by repealing the ACA aimed to move to a block grant structure in which states receive a fixed amount of federal dollars, allowing them to decide how funds are allocated, and shifting regulatory power primarily to states. These recent efforts, along with exclusions embedded in the ACA, both echo previous practices of policy devolution that effectively allowed certain states to exclude minorities from public programs.

Using state power to oppress in the wake of Reconstruction

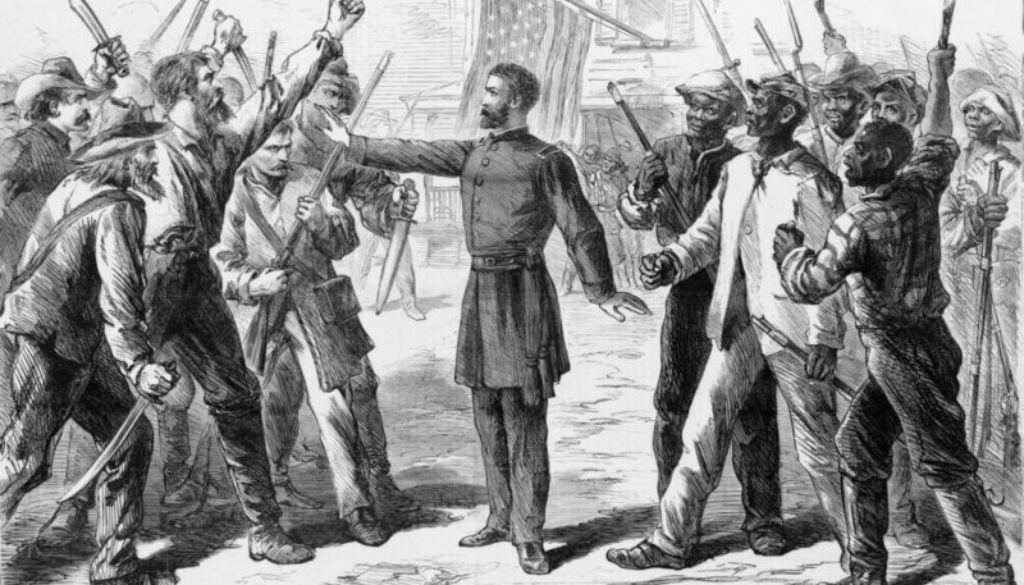

More than a century ago, a key backlash from the powerful white elite in Southern states occurred when Congress was passing federal civil rights acts and major programs after 1865 to give former slaves (also know as freedmen) access to the vote, good health care, education, training, and jobs. In his detailed history Black Reconstruction, the great sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois concluded in a grim chapter titled “Back Toward Slavery” that:

“It was the policy of the state to keep the Negro laborer poor, to confine him as far as possible to menial occupations, to make him a surplus labour reservoir and to force him into peonage and unpaid toil… Sickness, disease and death have been the widespread physical results of caste.”

Each defeated Confederate state changed its constitution and instated laws and practices that disenfranchised freedmen, ensuring that one-party rule led to a Southern Bloc in the Senate and House. This voting bloc gained unopposed seniority and thus chairmanships of major committees. They then widened states’ rights to include control over how to implement federal programs. Ironically, these strategic moves meant that the defeated white power elite of the Old South could increasingly block, bury, or amend legislation by the victorious Northern leaders, and they insisted that Congress delegate control over terms of enfranchisement, budgeting, and administration for federal programs to states.

Federal responses: the Freedmen’s Bureau and Maternal and Child health centers

In the first federal effort to redress the wretched health and living conditions of freed slaves, Congress created and funded the Freedmen’s Bureau. Its many branches offered extensive medical care and built 46 hospitals with more than 5,000 beds. W. E. B. Du Bois concluded, “The Freedmen’s Bureau was the most extraordinary and far-reaching institution of social uplift that America has ever attempted…. the greatest plan of reasoned emancipation yet proposed.”

However, Southern state officials used budgetary and administrative controls to undermine the Freedmen’s Bureau programs, including hospital care. Through the Black Codes, based on antebellum laws designed to create a marginalized caste of freedmen, they imposed numerous restrictions, such as requiring documents that many freedmen did not have, that the Civil Rights Act of 1866 tried to overturn.

Another federal program, the Sheppard-Towner Act of 1921, sought to address high rates of infant and maternal mortality among poor, rural, often “colored” women in the Southern states by funding thousands of child and maternal health care centers. State control over the implementation of the law, however, meant that benefits for minority mothers and infants were only a fraction of those provided to whites.

Whereas Southern politicians’ primary targets were African-Americans, states with increased Mexican immigration targeted immigrants as well. Referring to the Southwest, sociologist Cybelle Fox wrote, “State and local control in the administration of means-tested programs allowed for continued discrimination against blacks and Mexicans… Mexican aliens were blocked by citizenship restrictions and Mexican migrants by stiff residency provisions.”

Legacies for the Affordable Care Act

Our study shows how a historical pattern of Southern States embedding minority exclusion in policy influenced contemporary policies, from the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act (PRWORA), commonly known as “Welfare reform,” to the ACA. Immigrant eligibility for Medicaid continues to rely on distinctions across categories of immigrants, notably through the status of “qualified immigrant.” These categorical distinctions were created in the implementation of the 1996 welfare reform act, following conservative rhetoric stating the need to prevent the United States from becoming a “welfare magnet” and overrun with immigrants. The 1996 reform made immigrant status categories more complex, but also gave states greater leeway to “discriminate against legal immigrants in federal and state benefit programs, a power previously denied them by the courts.”

As a result of these policies, eligibility for social programs differs across immigrant categories. Qualified immigrants have the same access to ACA provisions as U.S. citizens do, but recently arrived immigrants have access only to the health care exchanges. Undocumented immigrants, including DACA recipients, cannot access any of the ACA provisions. Indeed, they are not eligible for Medicaid or insurance subsidies, nor are they allowed to purchase insurance plans on their own through the ACA healthcare exchanges.

While distinctions among immigrants were strengthened, the turn towards policy devolution since the 1996 welfare reform also gave states greater power to limit or increase access to public health care, thus exacerbating policy differences across states. Some states, such as California, have funded additional programs to cover unqualified immigrants. Others, however, have imposed additional requirements for immigrants to access health care. Wyoming, for example, has required immigrants and others to have 40 quarters of work history in the United States in order to be eligible for Medicaid. This state-level divergence continued through the ACA, when the 2012 U.S. Supreme Court decided to let states choose whether they wished to expand Medicaid. The court’s ruling echoes the same historical precedents of policy devolution: nearly three million individuals cannot access affordable health care, with the resulting coverage gap disproportionately affecting racial and ethnic minorities and immigrants. In 2017, only one out of the eleven former Confederate states chose to implement the Medicaid expansion. The ACA programs in the states of the former Confederacy often entail complex requirements, frequently changing procedures, and strict eligibility conditions reminiscent of tactics of de facto exclusion pursued by the defeated white elite in Confederate states 150 years ago.

Efforts to repeal and replace or simply weaken the Affordable Care Act show two political strategies in the repertoire of conservative lawmakers today: (1) defining or upholding categorical distinctions to create out-groups, and (2) pursuing the transfer of authority to state governments . For example, different proposals to repeal the ACA call for greater state control through block-granting, as well as stricter eligibility thresholds for low-income individuals. The more that control over health care devolves to the states, the less national and universal it will be. In such ways, intense conflict over removing barriers to universal access to health care reflect the longstanding legacy of historical racism in the nineteenth century as it affects discrimination against immigrants and others today.

About the authors

Mélanie Terrasse is currently pursuing a PhD in sociology and social policy at Princeton University. Her previous research has examined questions related to immigrant integration in France, as well as the intersection of US health care and immigration policy. She is currently working on her dissertation, which uses ethnographic methods to examine the implementation of a shared client database among a network of anti-poverty nonprofits in Central Pennsylvania.

Mélanie Terrasse is currently pursuing a PhD in sociology and social policy at Princeton University. Her previous research has examined questions related to immigrant integration in France, as well as the intersection of US health care and immigration policy. She is currently working on her dissertation, which uses ethnographic methods to examine the implementation of a shared client database among a network of anti-poverty nonprofits in Central Pennsylvania.

Donald W. Light is a visiting researcher at the Center for Migration and Development, Princeton University and professor of comparative health care systems and societal ethics at Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine. His articles on the institutional injustices of American health insurance have appeared in major journals.

Donald W. Light is a visiting researcher at the Center for Migration and Development, Princeton University and professor of comparative health care systems and societal ethics at Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine. His articles on the institutional injustices of American health insurance have appeared in major journals.

All comments will be reviewed and posted if substantive and of general interest to IAPHS readers.