Beyond the Boxes, Part 2: Defining Race and Ethnicity

Natalie Smith, Rae Anne Martinez, Nafeesa Andrabi, Andrea (Andi) Goodwin, Rachel Wilbur, Paul Zivich

This post is the second in a series we are writing about the use of race and ethnicity in population health research. This post covers definitional challenges and discusses why researchers must clearly state how they define race and ethnicity.

Rigorous population health research begins with a clearly stated research question, conceptual model or theory, and precisely defined exposures and outcomes. Authors commonly spend several paragraphs in the Introduction and Methods sections defining and contextualizing their exposures and outcomes. However, throughout our review of how race and ethnicity are used in population health, one of our primary insights has been that authors often do not state how they define race and ethnicity. Startlingly few articles provide explicit definitions of these concepts: of 350 randomly sampled articles from Epidemiology journals, we found only one that defined race and ethnicity.

Ultimately, we seem to take for granted that we know exactly what population health researchers mean when we say “I measured race and ethnicity.” We assume that our understandings of these concepts are universal across disciplines, place, and time. But that is simply not the case. Failing to define race and ethnicity makes it hard to compare findings across studies and often leaves us wondering what exactly findings pertaining to “race” or “ethnicity” really mean.

Defining the terms

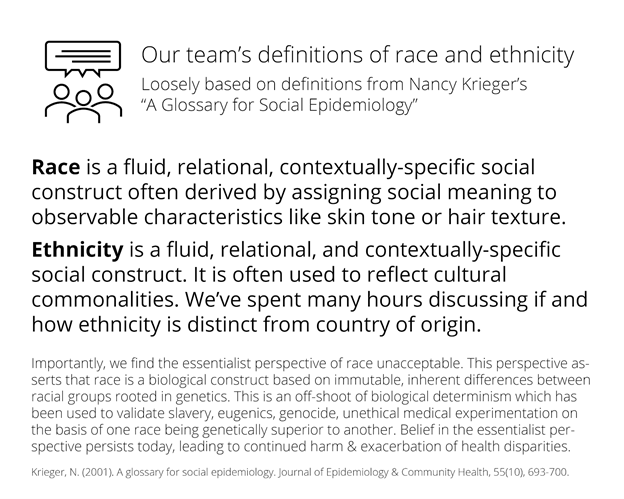

Our group’s definitions are shown in the following figure and are the foundation for subsequent posts. Importantly, these definitions may be different from what you use. Including these definitions serves to underscore a key point of our posts: it is crucial for researchers to clearly state and justify assumptions and choices around race and ethnicity in their work.

We ask ourselves the following guiding questions when conceptualizing race and ethnicity in our own research:

- How do you define race? How do you define ethnicity? How are your definitions for race and ethnicity similar or different? Do they overlap?

- Why is race and/or ethnicity important to your research question?

- Where do race and/or ethnicity fit into your conceptual model?

- In your manuscript, have you communicated your answers to questions #1, 2, and 3 clearly?

For us, answering these questions helped us discover conceptual gaps in our own work.

The need for establishing a shared understanding of race and ethnicity in population health research is illustrated by some challenges we’ve wrestled with in our work:

- Are Black and African American distinct identities? The current US census form does not distinguish between these two groups. Recent work in the New York Times and discussions on Twitter (e.g., here and here) and elsewhere have dug into this question, with a variety of opinions emerging. To our knowledge, there is no one clear or correct answer. In our work, we conceptualize Black as a racial identity, while we consider African American as a US-centered ethnicity that captures a shared heritage or history, such as ancestral legacy of slavery.

- To whom does Hispanic, Latino/a, Latinx refer? Are these ethnic or racial categories? While often used interchangeably, these US-centric terms have different foundations. Hispanic emphasizes strong connections to Spain (due to colonization), while Latino/a refers to folks from any country in Latin America currently residing in the US (and thus deemphasizes colonization, and excludes Spain). Latinx is an emergent term that first originated in LGBTQA online communities and is tightly tied to gender politics. A recent Pew report investigated perceptions of Latinx. We found it unsurprising that a highly heterogeneous group of people had varied opinions on their preferred term for ethnic identity. Hispanic, Latino/a, and Latinx are all pan-ethnic identities, and most individuals within those groups have more specific nuanced ethnic identities such as “Colombiano/a,” “Chicano/a,” “Nuyorican,” or “Tejano.” For a deeper dive into these differences, here are two readings (1) (2), or podcast options if you’d prefer to listen (1) (2).

- How do we best conceptualize Indigenous identity? Indigenous peoples are often relegated to the “other” category in large data sets. When they are included, it is typically as a blanket category. Common terms for Indigenous peoples of the unceded territory of the continental United States and Alaska include Native American, American Indian, and Alaska Native. Much like Hispanic and Latino terminology, these blanket terms can be problematic because there are more than 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States, each with distinct membership requirements, histories, and culture. Still more tribes are recognized by states or remain unrecognized by government entities. It may be more appropriate to speak of individual tribal communities as ethnic groups. For an example of how three tribal nations prefer to be identified, see the 2020 Cherokee Scholars’ Statement on Sovereignty and Identity. For a more in-depth exploration of Indigenous race and ethnicity, we suggest reading Kim Tallbear’s book Native American DNA.

There are no easy answers to the questions we’ve mentioned above, and this is just a small snapshot of the complexities of race and ethnicity that population health researchers must address. As researchers, simply knowing or acknowledging that race and ethnicity are socially constructed is not enough. We must continuously engage with the unique historical, social, and political contexts in which these categories have emerged and continue to evolve. These historical and contemporary processes of constructing boundaries around race and ethnicity are central to understanding health disparities in the US. We would be remiss to gloss over the tensions and contradictions that exist within contemporary meanings of race and ethnicity in favor of clear, reductive boundaries

So we call on all health scholars to define your terms and look into the conceptual gaps these definitions may bring up, because these are the necessary first steps for all of us to do better in our population health research.

Our next posts will present guiding questions and resources related to measurement, analysis, and interpretation of race and ethnicity findings.

To explore these topics further, listen to the IAPHS podcast “Sick Individuals, Sick Populations.”

Resources:

- TallBear, K. (2013). Native American DNA: Tribal belonging and the false promise of genetic science. U of Minnesota Press.

- Krieger, N. (2001). A glossary for social epidemiology. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 55(10), 693-700.

All comments will be reviewed and posted if substantive and of general interest to IAPHS readers.