Equitable Population Health Improvement Requires Community Ownership

Vinu IlakkuvanWhen we’re seeking to advance population health, ensuring that the communities we work with are driving population health improvement efforts is vital. Achieving true community ownership requires not just collaborating with but also deferring to those who live, work, and play in these communities.

What is Community Ownership?

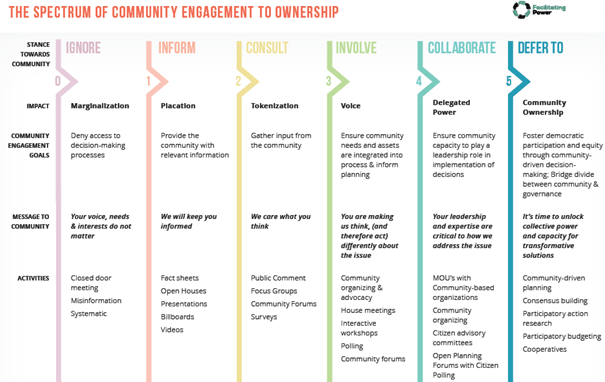

As outlined in the figure below from Facilitating Power, community ownership moves beyond merely engaging the community to “foster[ing] democratic participation and equity through community-driven decision making,” thus bridging the gap between community and governance. The goal here is to achieve “direct participation by impacted communities in the development and implementation of solutions and policy decisions that directly impact them.”

Source: Modified version of figure in The Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership by Facilitating Power

What is the Value of Community Ownership?

As noted in the Vital Conditions for Community Health and Well-Being framework, this kind of meaningful and direct participation helps foster a sense of belonging and power to impact one’s community, which in turn “enhances mental well-being, reinforces healthy behaviors, and encourages [further] community participation and vibrancy.” Community ownership thus offers both individual-level benefits to those involved as well as societal-level benefits to the larger community in terms of the new policies and systems changes that result.

Community ownership is also essential to fostering equity. Here, it’s important to consider both equity of process (i.e., ensuring the participation truly is democratic, such that all members of the community have opportunity to participate and exercise agency and power) and equity of outcomes (i.e., as noted in PolicyLink’s Equity Mainfesto, this kind of “just and fair inclusion” is more likely to lead to “a society in which all can participate, prosper, and reach their full potential”).

The exercise of meaningful agency and power by members of BIPOC, low-income, and other marginalized communities can help disrupt the unequal power dynamics that underlie and reinforce structural racism. This disruption occurs both directly— via the inclusion of those who have historically been excluded and often harmed by existing policies and policymaking approaches —and indirectly, because policy and systems changes driven by these communities are more likely to benefit them.

What Does Community Ownership Look Like in Practice?

It can be hard to think about something like community ownership in the abstract. To operationalize the concept, here is a (by no means comprehensive) list of concrete strategies and approaches that I think fall under the umbrella of community ownership.

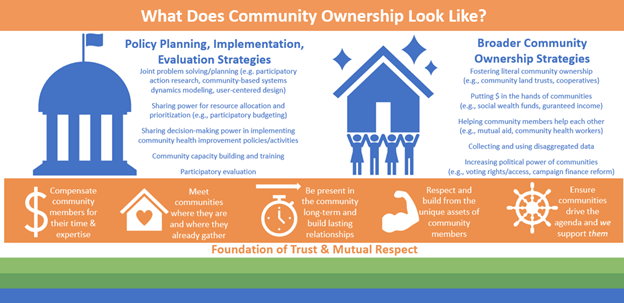

First is a foundation of:

- Demonstrating respect for communities and community members, including by compensating them for their time, particularly when we’re working with low-income, BIPOC, and other marginalized groups. It is unreasonable (and inequitable!) to ask community members to invest substantial time, effort, and expertise in community improvement efforts without being paid.

- Earning the trust of communities and community members, including by meeting them where they are and in the spaces they already gather, by being present in the community long-term and building lasting relationships, by respecting and building from the assets of particular communities and community members, and by ensuring community members are driving the agenda and that we are supporting them instead of vice versa.

Building on top of that foundation, community ownership strategies related to policy planning, implementation, and evaluation include:

- Joint problem solving and planning approaches (e.g., participatory action research, community-based systems dynamics modeling, and user-centered design approaches to developing policies)

- Power sharing in resource allocation and prioritization (e.g., participatory budgeting)

- Sharing decision-making power in the implementation of community health improvement policies and activities

- Community capacity-building via leadership and other training

- Evaluating projects in a participatory way in order to understand what is working, what is not, and what needs to change from the perspective of those most directly impacted by the project

Broader community ownership strategies include:

- Fostering literal community ownership (e.g., community land trusts, cooperatives)

- Putting money directly in the hands of communities (e.g., social wealth funds, guaranteed income)

- Helping community members help each other through approaches both informal (e.g., mutual aid) and more formal (e.g., community health workers)

- Collecting and using disaggregated data (e.g., by race/ethnicity) that goes beyond broad subgroups to understand the nuances and the impacts of varied life experiences, cultures, and other factors

- Increasing the political power of communities (e.g., expanding voting rights and access, campaign finance reform)

One example of community ownership from my own work is Washington DC’s multisector School Mental Health Stakeholder Learning Community (SLC), composed of education and healthcare practitioners, school administrators, researchers, policymakers, and family advocates. The SLC was formed to identify and pursue systems-level improvements to improve school mental health and equity for students in DC. However, the members of the SLC quickly realized this work should be driven by those most impacted by the system. The SLC thus partnered with the Social System Design Lab at Washington University in St. Louis to engage in Community Based System Dynamics (CBSD) group model-building with students, families, and teachers in DC public schools. This participatory method supports communities in developing a shared understanding of how the system functions and identifying solutions based on these insights.

One central insight across all groups was that racism pervaded the entire structure of the school mental health system in DC and that systems change needs to begin with resolving the tension between high-stakes testing, exclusionary discipline and criminalization of youth, and inadequate behavioral health services. In addition, the CBSD approach is building capacity for systems analysis among students, families, and teachers through training, co-design, and facilitation, thus laying a foundation for stronger grassroots advocacy around policies to strengthen the school mental health system and counter structural racism within it.

Walking the Talk

Pursuing community ownership strategies in our work with communities is vital, but not sufficient. We must consider how to do so in our own lives and organizations as well. For example, the Participatory Budgeting Project ensures employees determine a piece of their own organization’s budget. This is a great example of how to begin “walking the talk.” As population health researchers and practitioners, what are other ways that we can “walk the talk” to incorporate community ownership into our work?

This blog post is based on the June issue of PoP Health Perspectives, PoP Health’s monthly email newsletter. You can see the June issue and subscribe for future issues at pophealthllc.com/newsletter.

All comments will be reviewed and posted if substantive and of general interest to IAPHS readers.