Beyond the Boxes, Part 3: Measuring Race and Ethnicity to Align with Your Research

Natalie Smith, Rae Anne Martinez, Nafeesa Andrabi, Andrea (Andi) Goodwin, Rachel Wilbur, Paul Zivich

This post is the third in a series we are writing about the use of race and ethnicity in population health research. Our second post covered the challenges of defining race and ethnicity. This post presents guiding questions you can use to measure race and ethnicity in ways that align with your stated research question and conceptual model.

“…Salvador, a restaurant worker in New York, identifies his race as Puerto Rican. Phenotypically, he is dark-skinned with Indigenous features, leading some Americans to view him as Black. He believes that Americans view him as Hispanic, based on his accent and name. Yet on the census, Salvador checks White for his race because no listed option fits his identity and in Puerto Rico his mixed racial ancestry allowed him to consider himself closer to White than to Black.” (Roth, 2016, The multiple dimensions of race)

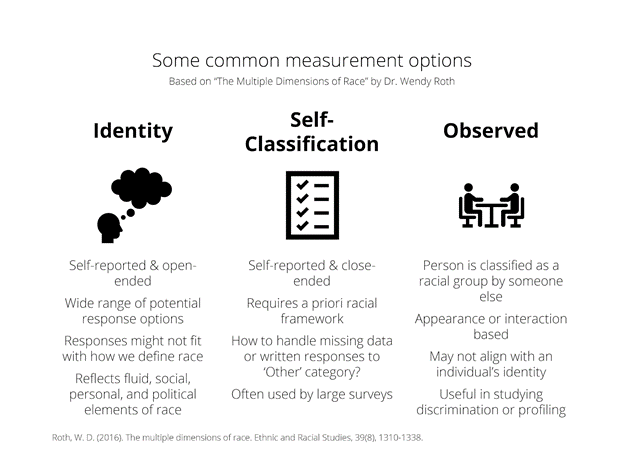

Over the past few months, we’ve examined how population health researchers have measured race and ethnicity in their studies. To do this, we collected information on how race was measured using dimensions proposed by Dr. Wendy Roth as a guideline. Roth asserts that race is a fluid, multifaceted identity that can be assessed through numerous dimensions. Each dimension captures slightly different, and sometimes conflicting, information about race. Some example dimensions include racial identity, racial self-classification, and observed race (see Figure below).

Overall—across disciplines and time—our investigation found that a vast majority of studies simply do not include enough information for us to know how race or ethnicity was measured. In other words, most of the time the measure of race or ethnicity was “not stated or unclear.” As researchers, the lack of description and clarity were disappointing.

In the above figure, we highlight dimensions of race commonly used in population health that researchers may find useful in their own work. Here’s some more explanation on these terms.

Racial Identity is a self-reported, open-ended measure. When researchers ask for someone’s racial identity, we might receive responses that don’t match how we would define race because racial identity is fluid, personal, and political. Our understandings of race and ethnicity vary by person, place, and time. However, we often impose our own assumptions onto others when we clean and code racial identity data.

For example, when working with secondary data, how would you recode individuals who responded “Puerto Rican” or “Iranian” when asked an open-ended question about their racial identity? If you only want to receive information based on your own assumed racial categories (i.e., racial self-classification), or you don’t want to analyze a wide range of racial and ethnic identities that may not fit with your definition, then racial identity is probably not the dimension of race you want to measure! This is exactly why we argue that it is critical to clearly define race and ethnicity, and state their relevance to your research question, before you collect your own data or analyze secondary data.

Racial Self-Classification is a self-reported, close-ended measure where individuals are asked to identify themselves within a given racial schema. Respondents might experience cognitive dissonance if they don’t clearly see themselves fitting within that schema. Some may reject the racial schema all together. When we consider missing data for racial self-classification, we should ask ourselves, “Is this person’s data missing because they fundamentally do not see themselves within these categories?”

Many self-classification questions have the option of “Some other race: ______” where respondents are asked to fill in their race if none of the given categories apply. Is this question really racial self-classification, or is it actually an identity/self-classification hybrid (i.e., is it the same as respondents filling in an open-ended question under “Some other race”)? What kind of information are we collecting, and is that information consistent across individuals, groups, and contexts?

Observed Race is captured when an individual is assigned a racial identity by someone else. Individuals may “read” the total sum of another’s body—their skin tone, hair texture, eye color, bone structure, visual cultural cues, and so on—to ascribe a racial category. Think about when a health care professional assigns a patient’s race at intake in the emergency room without asking the patient how they identify. In addition to visual cues, an individual may “read” interactions—accent, gesturing, body language, and so on—to assign individuals into a perceived racial category. Think about a telephone-based survey where an individual is assigned a racial category based on accent, vocabulary, and cadence alone. Especially in studies that rely on healthcare data, we may be analyzing observed race without even knowing it (e.g., electronic health records).

Purposeful measurement of race and ethnicity is important because measurement is indelibly linked to results. Without a proper understanding of how studies have measured race and ethnicity, how can we synthesize findings across studies and draw overarching conclusions about racial and ethnic inequality in the US?

Our team’s guiding questions for measuring race and ethnicity are:

- What dimension(s) of race or ethnicity is(are) most relevant to your research question?

- If you are collecting your own data, what kind of question(s) will you use to measure your chosen dimension(s) of race and ethnicity?

- If your work uses existing data, how does that data source conceptualize and measure race and ethnicity?

- Is it consistent with your research question?

- If it is not, what are the limitations or resultant biases?

- Measurement-specific questions to consider, specifically around self-report questions, include:

- Is the self-report question open- or close-ended?

- If close-ended, what is the list of potential response options? These racial and ethnic groups are the product of social forces, conscious individual decisions, and federal reporting requirements (themselves based on social forces and individual decisions).

- Are participants asked what group they MOSTLY consider themselves? Or should they be asked to report on ALL of the groups they consider themselves to be?

- In your manuscript, have you unambiguously communicated what measure(s) you used?

Given how important large datasets are to population health research, our group has been working on a living document outlining how large population-wide datasets measure race and ethnicity. We’ve made this document available to view. This form contains the datasets that our team has used in the past, but there are many more datasets out there. We’ve created a short form for researchers to fill out with other datasets so that we can expand this resource. Relatedly, the Multiple Components of Race Data Library contains information on large datasets that measure race and ethnicity in multiple ways.

The next post in our series will discuss our guiding questions around the use of race and ethnicity in analyses.

Resources

- Roth, Wendy D. (2016) The multiple dimensions of race, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 39:8, 1310-1338, DOI: 10.1080/01419870.2016.1140793

- Multiple components of race data library

- Our resource outlining how race/ethnicity are measured in existing pop health datasets. Please add other datasets using this form link.

- OMB measurement rule: Federal Register, 1997; slide on OMB Standards

All comments will be reviewed and posted if substantive and of general interest to IAPHS readers.