Racism in the Time of COVID-19

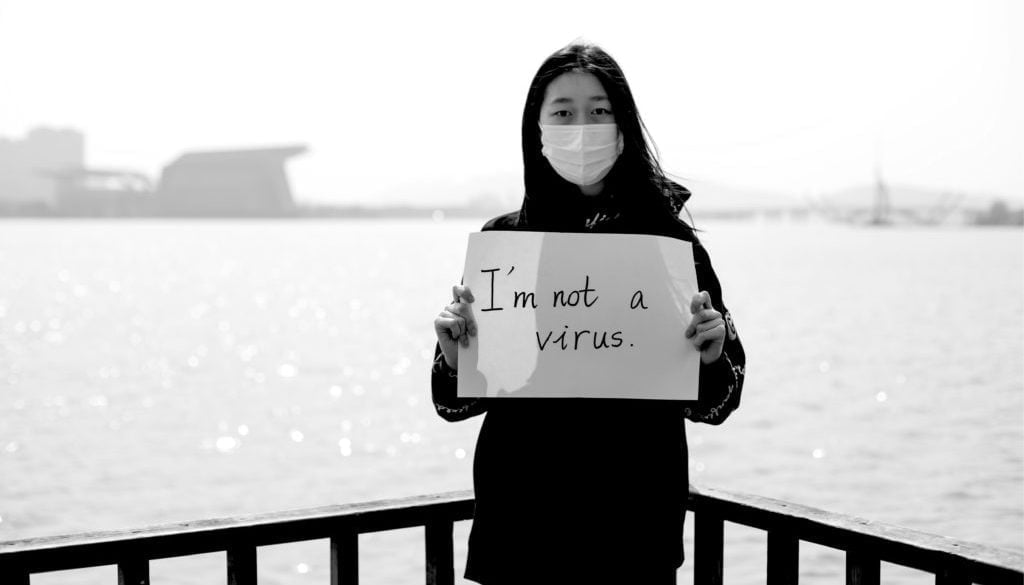

Zinzi Bailey, Sharrelle Barber, Whitney Robinson, Jaime Slaughter-Acey, Chandra Ford, Shawnita Sealy-JeffersonIn December 2019, the first cases of “a pneumonia of unknown cause” were reported in Wuhan, China, a port city of 11 million people in the central Hubei province. As COVID-19 — an infectious disease caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-Cov-2 — spread and reached the status of a pandemic by March 11, 2020, so did racist and xenophobic rhetoric around its origins, and instances of racial stigmatization and violence against people of Asian descent. The bigoted rhetoric of U.S. President Trump who, in official statements to the national press dubbed COVID-19 the “Chinese Virus,” further fueled these sentiments and acts of violence.

This kind of overt racism and racialization of disease is not new in the U.S.; it is just the newest iteration of the ways Black, Latinx, Asian, and various immigrant groups have been viewed as “vectors of disease.” In 1899, for instance, renowned sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois highlighted the racialization of tuberculosis in his pathbreaking work The Philadelphia Negro:

“Particularly with regard to consumption, it must be remembered that Negroes are not the first people who have been claimed as its peculiar victims; the Irish were once thought to be doomed by that disease — but that was when Irishmen were unpopular.”

Other recent examples include syphilis in the U.S. south in the early 1900s, the domestic and global AIDS epidemic, and the cholera outbreaks in Venezuela in 1992 and in Haiti in 2011. Each was seen, to some extent, as rooted in cultural or other characteristics of racial/ethnic minority populations, a perception fanned by media reports and research approaches.

. . .while COVID-19 is indiscriminate in its transmission, its propagation within a society steeped in structural racism will undoubtedly, as we are already beginning to see, lead to disproportionate impacts among marginalized racial groups in this country.

But racialization of the COVID-19 pandemic was just the beginning. As this public health crisis unfolds in the U.S., it is making even more visible the interlocking systems of racism and marginalization that have their origins in the genocide of Native American peoples and enslavement of African peoples, which together constitute the foundation upon which the nation was built. Thus, while COVID-19 is indiscriminate in its transmission, its propagation within a society steeped in structural racism will undoubtedly, as we are already beginning to see, lead to disproportionate impacts among marginalized racial groups in this country.

Undetected Cases Among Racially Marginalized Communities

By any measure, the federal government has been reckless, failing to provide a coordinated response to the forewarned pandemic, including allowing severe inadequacies in testing and surveillance. Some experts believe that identified cases represent the tip of the iceberg — revealing only around 12% of the actual number of people infected with the virus. Not only that, undercounting is likely to be even more pronounced among marginalized racial groups with less access to healthcare. Moreover, piecemeal testing practices that favor asymptomatic basketball players, movie stars, and members of Congress over individuals presenting with clinical symptoms will lead to “silent epidemics” among communities of color. Finally, even though some (but not all) case data are disaggregated by geography, age group, and sex, most surveillance systems (with the exception of a few), are not reporting race/ethnicity, socioeconomic, or other sociodemographic information, which prevents the documentation of racial inequalities. Taken together, the failure to test and quickly isolate people with COVID-19 and lack of universal socio-demographic surveillance data means that COVID-19 outbreaks can grow unchecked in marginalized communities of color.

Structural Constraints to Implementing Prevention Strategies

No pandemic affects each subpopulation in exactly the same way. Therefore, comprehensive prevention and intervention strategies should not rely upon a one-size-fits-all approach. While the basic public health recommendation of frequent hand-washing is low-cost and relatively accessible, Black, indigenous, and people of color are over-represented in racially and economically segregated communities with substandard housing conditions and unsafe drinking water that make hand hygiene more difficult. Additionally, without any universal protections against municipal water access being shut off for non-payment (or any other reasons), some may not even have access to running water. Moreover, if an individual contracts the virus, crowded housing conditions make self-isolation and quarantine virtually impossible, which leads to further transmission within families and communities. Finally, though social distancing is a scientifically-proven strategy to “flatten the curve”, it is nevertheless a privilege, and a strategy to which low-wage, “essential” workers, who are disproportionately people of color, have been unable to adhere to either because of being mandated to work (e.g., grocery store cashiers) or because of fear of lost wages or permanent unemployment.

Other Intersections with Structural Racism

Other Intersections with Structural Racism

- Racial Inequities in Chronic Conditions: Across outcome, time, and place, racial/ethnic health disparities are ever-present as a result of social inequity. Not only are Blacks and other marginalized racial/ethnic groups more likely to die younger, they are also more likely to develop chronic conditions like cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and HIV/AIDSat at earlier ages — inequities that are partly driven by structural racism — which puts these groups at higher risk for mortality during this crisis. This is particularly true in the South, a region of the country with the highest proportion of Blacks, high prevalence of underlying chronic conditions, and a history rooted in the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow.

- Healthcare Access and Implicit Bias/Discrimination: There are known racial/ethnic inequities in the ability to access healthcare, due in part but not entirely to lower rates of health insurance, poorer access to high quality facilities and pharmacies in marginalized, often racially segregated, communities. Moreover, Blacks and other marginalized racial groups also experience differential treatment, e.g., through implicit biases and discrimination based on race/ethnicity that affect the quality of care diverse patients receive. This may put them at a disadvantage when seeking testing, accurate diagnosis, medications, and high-quality, timely care. And as healthcare facilities around the country begin to reach capacity, access to limited, life-saving equipment such as ventilators will be left up to health professionals, a scenario in which racial bias and discrimination will inevitably lead to racialized opportunities for survival.

- Racial Residential Segregation: Due to historical and contemporary discriminatory housing practices (e.g. redlining) and decades of systematic disinvestment, the racially segregated neighborhoods that are less likely to have access to quality healthcare, access to essential pharmaceuticals, and optimal housing conditions are the same neighborhoods with limited health-promoting neighborhood environments (e.g., access to green space, healthy foods, low violence, high social capital). This may confer, on average, higher stress levels and poorer physical and mental health, leading, perhaps, to higher susceptibility to infection.

- Mass Incarceration/Detention and State-Sanctioned Surveillance: The collateral damage to individual and community health caused by our carceral state — incarcerating over 2.2 million people in 2018 — has been well-documented, with Black and Latinx individuals disproportionately impacted. People confined to prisons, jails, and immigrant detention centers are at heightened risk of experiencing the devastating impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic due to (1) close, shared quarters, (2) structural constraints on hygiene, and (3) the preponderance of underlying health conditions. Further, immigrant groups, whether documented or undocumented, are under surveillance and in danger of experiencing discriminatory policing by ICE. Many immigrants avoid seeking healthcare as a legitimate response to racist anti-immigrant policies, including ICE detention and public charge rules. Releasing detained persons is a viable option for reducing the efficiency with which the epidemic spreads; however, it is critical to develop prevention plans that address how release will impact the families and communities to which they will return.

- Racism Beyond Our Borders: This pandemic is global, and so, too, is racism. The disproportionate impact among marginalized racial groups, however those groups are defined in each society, will be experienced beyond the United States. For example in Brazil, whose Black and mixed-race population exceeds 50% and who are more likely to live in segregated “favela” areas, will be disproportionately impacted by the outbreak. Many favela communities lack access to running water and sanitation, and workers are forced to continue to work despite the rising threat. Crowding and other issues will exacerbate these issues. Migrant and refugee communities in European countries face similar challenges.

A Critical Race Response to the Pandemic

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to unfold, our collective analysis of and response to this global crisis must go beyond mainstream biomedical, behavioral, and psychosocial explanations of disproportionate impact and be grounded in an explicit structural racism lens. Applying frameworks such as Critical Race Theory and Intersectionality will be necessary in order to examine the ways existing power structures and underlying racial inequities will produce both short- and long-term consequences. We must ensure that data collection on COVID-19 is linked to more complete information on race/ethnicity, immigrant status, and indigenous status, and that it captures the social determinants of health and explicit indicators of structural racism (e.g. racial residential segregation). Furthermore, quantitative research must be coupled with qualitative data that captures the narratives of individuals most directly impacted by the pandemic.

We must ensure that data collection on COVID-19 is linked to more complete information on race/ethnicity, immigrant status, and indigenous status, and that it captures the social determinants of health and explicit indicators of structural racism (e.g. racial residential segregation).

Finally, as a field with a mandate to ensure the public’s health, efforts to mitigate the effects of this pandemic must work in tandem with our ongoing commitment to dismantling the structural and institutional drivers of health inequity that existed before this crisis. We have an ethical and moral responsibility to harness our collective strength, speak truth to power, and demand that racial equity and social justice be central to our response to this pandemic and beyond. The stakes are too high to sit on the sidelines. This is a matter of life and death and we must all act accordingly.

April 9, 2020 @ 9:35 pm

https://www.alaskajournal.com/2020-04-07/opinion-finance-co-chair-doesnt-trust-rural-alaska-early-pfd

See comments by legislator in Alaska regarding the small (Native) communities in Alaska.

April 9, 2020 @ 5:18 pm

Safety Net Activists, hit the road running when we found cornavirus had pandemic status. I thank you for speaking to our inner hearts and thoughts as my colleagues and I manned- down our conference phone calls and pulled together an emergency response document to assist the street/sheltered homeless population recommendation to prevent an escalated number of fatalities regarding cornavirus person to person ephdemic transmission. We found no prevention protocol to deal with the most variable population the homeless. Many grassroots have joined in force. We all need to join hands and fight against racism built into our government systems and hold person’s responsible accountable for what happened across our country. Permanent housing and quality health services are a must for the most variable citizens in our country. To ensure the health of others. Well done response and I thank you for it.