Indigenous Data Sovereignty Network: Filling an Important Research Gap

Desi Rodriguez-LonebearThis is part two of our interview with Desi Rodriguez-Lonebear. We wanted to learn more about the USIDSN, which Rodriguez-Lonebear founded in 2016.

Can you describe the U.S. Indigenous Data Sovereignty Network (USIDSN) for us? What’s unique about it and what gap does it fill?

The USIDSN is a community of practice that supports Indigenous data sovereignty through data governance focused research, policy advocacy, and education. Indigenous data sovereignty is the right of a nation to govern the collection, ownership, and application of its own data. It derives from tribes’ inherent right to govern their Peoples, lands, and resources.[i]

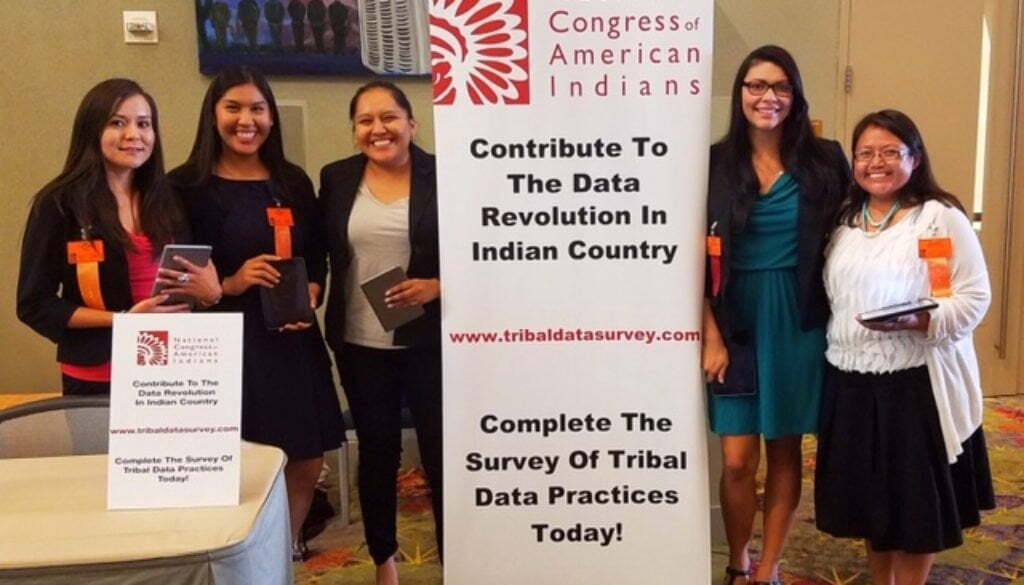

In 2016, I co-founded the USIDSN with my colleague Stephanie Russo Carroll. We started as an interdisciplinary group of Indigenous researchers and tribal policy makers collaborating on research, exploring the data needs of tribal communities, and collectively advancing Indigenous-driven data solutions. The USIDSN is unique–it’s the only collective focused on Indigenous-driven data solutions in the U.S. spanning a wide range of fields, including demography, population health, environmental science, and economic development.

With over three hundred members now in the Network, we leverage the collective knowledge of diverse stakeholders to advocate on the local, national, and international levels for Indigenous data sovereignty. We also develop relevant resources and educational materials to support the data needs of Indigenous communities.

The USIDSN is unique–it’s the only collective focused on Indigenous-driven data solutions in the U.S. spanning a wide range of fields, including demography, population health, environmental science, and economic development.

We encourage anyone, Indigenous or non-Indigenous, interested in Indigenous data sovereignty to join the Network. For those interested in a more detailed overview of Indigenous data sovereignty in the U.S., we offer several short-courses as part of the University of Arizona’s “January in Tucson” program for Indigenous governance. Please visit https://usindigenousdata.arizona.edu.

What are some of the uses of these data in your own work, and could they be used to inform research and intervention work in population or public health?

Much of my research and advocacy centers on accurate and accessible tribal population data. My first research post was in Aotearoa/New Zealand where I supported the development of the first tribal census project conducted by a Māori tribe for a Māori tribe. Our diverse research team included academics alongside tribal leaders, elders, and youth. Serving on this project honed my understanding of research partnerships driven by strong tribal governance practices. I applied these lessons to research with tribes in the US, including my own tribe, the Northern Cheyenne Nation.

My most challenging and rewarding project thus far involved working with my tribe on one of the largest surveys of American Indian youth. We trained an army of youth surveyors, worked with local schools, and partnered with twelve community organizations to survey over 2,000 Cheyenne young people. We developed culturally grounded indicators of well-being that emerged from Cheyenne youth and were supported by strong tribal governance practices. These data collected by Cheyenne youth for Cheyenne youth established a much-needed baseline of the future of our tribe across Western and Cheyenne metrics of well-being. Drawing on this experience and others, I have had the honor of advancing Indigenous quantitative methods alongside Indigenous communities over the last ten years.

… the existing datasphere on Indigenous Peoples has been carefully curated by non-Indigenous entities, namely federal agencies and universities whose efforts have yielded significant amounts of data collected about but not by Indigenous Peoples.

My current focus is on tribal demography. Native Nations have long been concerned with tribal population data because a nation’s most precious resource is its people—past, present, and future. Yet, the existing datasphere on Indigenous Peoples has been carefully curated by non-Indigenous entities, namely federal agencies and universities whose efforts have yielded significant amounts of data collected about but not by Indigenous Peoples. The U.S. Census, for example, has asked for tribal affiliation since the 1970 census, yet tribal leaders continue to push back against the accuracy and utility of federal enumeration pointing to the vast undercounts of their tribal populations decennial after decennial.

Administrative data linkage with tribal data is an area of emerging research that holds great promise for Indigenous data sovereignty if executed on tribal terms.

Now is an exciting time for tribal demography, however, because tribes are moving towards proactive rather than reactive efforts to challenge official statistics. I am currently engaged in several tribal demography projects using tribal enrollment records, which are the core of tribal data systems, including (1) evaluating the utility of US Census data for tribes, specifically how federal counts differ in size and composition from tribal counts; (2) developing stronger tribal vital statistics systems and health outcomes data reporting; and (3) conducting population projections to determine sustainability of tribal populations using various citizenship criteria. These projects are all conducted through an Indigenous data sovereignty lens, opening up the possibility for data linkage with federal datasets and other data to support tribal governance. Administrative data linkage with tribal data is an area of emerging research that holds great promise for Indigenous data sovereignty if executed on tribal terms.

What else would you like people to know about the Network and about Indigenous data?

I want to close by issuing a call to action: the Indigenous data revolution requires skilled data warriors! Towards this end, federal agencies should consider sustainable investment in data infrastructure and capability building as key aspects of the federal trust responsibility to Native Nations. So too should population health researchers and academics writ large ask themselves, “What can I do to support the Indigenous data revolution?”

First, researchers should proceed with a critical eye in using existing federal data on Indigenous Peoples. Second, support the access of existing data and the collection of new data by Indigenous communities. Third, advocate against academic devaluation of research and publications that do not meet standard academic metrics. The academy should consider utility to the community of origin as a key metric of a research project’s success and scholarly contribution. Fourth, invest in Indigenous data warriors at all levels from Tribal College students to PhD students. [i]

[i] Rainie, S. C., Rodriguez-Lonebear, D., & Martinez, A. (2017). Policy Brief: Indigenous Data Sovereignty in the United States. Tucson: University of Arizona Native Nations Institute.

All comments will be reviewed and posted if substantive and of general interest to IAPHS readers.